|

He prepared for a career in ministry, but switched to an academic career as a writer and teacher. Early education by his father, Daniel Malthus, introduced him to the writing of William Godwin and the French revolutionary, the Marquis de Condorcet, on the "perfectibility of man." They suggested that population growth was a positive sign of human progress, and was not a threat to future improvement. Robert rejected the optimism of his father and the perfectionists, and published his rebuttal in its first of six editions in 1798. The first was anonymous, but all of the others were named and were much longer than the first. He also contributed to the theory of rent and debates on the Corn Laws. AN ESSAY ON THE

PRINCIPLE OF POPULATION, BY THOMAS MALTHUS LONDON, 1798. Preface THE

following Essay owes its origin to a conversation with a

friend, on the subject of Mr Godwin's essay on 'Avarice and

Profusion' in his Enquirer.

The discussion started the general question of the future

improvement of society. and the Author at first sat down with

an intention of merely stating his thoughts to his friend,

upon paper, in a clearer manner than he thought he could do in

conversation. But as the subject opened upon him, some ideas

occurred, which he did not recollect to have met with before;

and as he conceived that every least light, on a topic so

generally interesting, might be received with candour, he

determined to put his thoughts in a form for publication… CHAPTER 1

It has been said that the great

question is now at issue, whether man shall henceforth start

forwards with accelerated velocity towards illimitable, and

hitherto unconceived improvement, or be condemned to a

perpetual oscillation between happiness and misery, and

after every effort remain still at an immeasurable distance

from the wished-for goal.

I have thus sketched the general outline of the argument, but

I will examine it more particularly, and I think it will be

found that experience, the true source and foundation of all

knowledge, invariably confirms its truth. CHAPTER 2

I SAID that population, when unchecked, increased in a

geometrical ratio, and subsistence for man in an arithmetical

ratio. Let us examine whether this position be just. I

think it will be allowed, that no state has hitherto existed

(at least that we have any account of) where the manners were

so pure and simple, and the means of subsistence so abundant,

that no check whatever has existed to early marriages, among

the lower classes, from a fear of not providing well for their

families, or among the higher classes, from a fear of lowering

their condition in life. Consequently in no state that we have

yet known has the power of population been left to exert

itself with perfect freedom. . . .

Sixth Edition, 1826

Book I, Chapter IIOf the General Checks to Population, and the Mode of their OperationThese checks to population, which are constantly operating with more or less force in every society, and keep down the number to the level of the means of subsistence, may be classed under two general heads—the preventive, and the positive checks The preventive check, as far as it is voluntary, is peculiar to man, and arises from that distinctive superiority in his reasoning faculties, which enables him to calculate distant consequences. The checks to the indefinite increase of plants and irrational animals are all either positive, or, if preventive, involuntary. But man cannot look around him, and see the distress which frequently presses upon those who have large families; he cannot contemplate his present possessions or earnings, which he now nearly consumes himself, and calculate the amount of each share, when with very little addition they must be divided, perhaps, among seven or eight, without feeling a doubt whether, if he follow the bent of his inclinations, he may be able to support the offspring which he will probably bring into the world. In a state of equality, if such can exist, this would be the simple question. In the present state of society other considerations occur. Will he not lower his rank in life, and be obliged to give up in great measure his former habits? Does any mode of employment present itself by which he may reasonably hope to maintain a family? Will he not at any rate subject himself to greater difficulties, and more severe labour, than in his single state? Will he not be unable to transmit to his children the same advantages of education and improvement that he had himself possessed? Does he even feel secure that, should he have a large family, his utmost exertions can save them from rags and squalid poverty, and their consequent degradation in the community? And may he not be reduced to the grating necessity of forfeiting his independence, and of being obliged to the sparing hand of Charity for support? The positive checks to population are extremely various, and include every cause, whether arising from vice or misery, which in any degree contributes to shorten the natural duration of human life. Under this head, therefore, may be enumerated all unwholesome occupations, severe labour and exposure to the seasons, extreme poverty, bad nursing of children, great towns, excesses of all kinds, the whole train of common diseases and epidemics, wars, plague, and famine. On examining these obstacles to the increase of population which I have classed under the heads of preventive and positive checks, it will appear that they are all resolvable into moral restraint, vice, and misery. Of the preventive checks, the restraint from marriage which is not followed by irregular gratifications may properly be termed moral restraint.

Book IV, Chapter VIIIPlan of the gradual Abolition of the Poor Laws proposedIf the principles in the preceding chapters should stand the test of examination, and we should ever feel the obligation of endeavouring to act upon them, the next inquiry would be, in what way we ought practically to proceed. The first grand obstacle which presents itself in this country is the system of the poor-laws, which has been justly stated to be an evil, in comparison of which the national debt, with all its magnitude of terror, is of little moment… I should propose a regulation to be made, declaring, that no child born from any marriage, taking place after the expiration of a year from the date of the law, and no illegitimate child born two years from the same date, should ever be entitled to parish assistance. And to give a more general knowledge of this law, and to enforce it more strongly on the minds of the lower classes of people, the clergyman of each parish should, after the publication of banns, read a short address, stating the strong obligation on every man to support his own children; the impropriety, and even immorality, of marrying without a prospect of being able to do this; the evils which had resulted to the poor themselves from the attempt which had been made to assist by public institutions in a duty which ought to be exclusively appropriated to parents; and the absolute necessity which had at length appeared of abandoning all such institutions, on account of their producing effects totally opposite to those which were intended… With

regard to illegitimate children, after the proper notice had

been given, they should not be allowed to have any claim to

parish assistance, but be left entirely to the support of

private charity. If the parents desert their child, they ought

to be made answerable for the crime. The infant is,

comparatively speaking, of little value to the society, as

others will immediately supply its place. Its principal value

is on account of its being the object of one of the most

delightful passions in human nature—parental affection. But if

this value be disregarded by those who are alone in a capacity

to feel it, the society cannot be called upon to put itself in

their place; and has no further business in its protection

than to punish the crime of desertion or intentional ill

treatment in the persons whose duty it is to provide for it… In Sweden, from the dearths which are not unfrequent, owing to the general failure of crops in an unpropitious climate and the impossibility of great importations in a poor country, an attempt to establish a system of parochial relief such as that in England (if it were not speedily abandoned from the physical impossibility of executing it) would level the property of the kingdom from one end to the other, and convulse the social system in such a manner, as absolutely to prevent it from recovering its former state on the return of plenty. Book IV, Chapter XIVOf our rational Expectations respecting the future Improvement of Society… If the principles which I have endeavoured to establish be false, I most sincerely hope to see them completely refuted; but if they be true, the subject is so important, and interests the question of human happiness so nearly, that it is impossible they should not in time be more fully known and more generally circulated, whether any particular efforts be made for the purpose or not.Among the higher and middle classes of society, the effect of this knowledge will, I hope, be to direct without relaxing their efforts in bettering the condition of the poor; to shew them what they can and what they cannot do; and that, although much may be done by advice and instruction, by encouraging habits of prudence and cleanliness, by discriminate charity, and by any mode of bettering the present condition of the poor which is followed by an increase of the preventive check; yet that, without this last effect, all the former efforts would be futile; and that, in any old and well-peopled state, to assist the poor in such a manner as to enable them to marry as early as they please, and rear up large families, is a physical impossibility. This knowledge, by tending to prevent the rich from destroying the good effects of their own exertions, and wasting their efforts in a direction where success is unattainable, would confine their attention to the proper objects, and thus enable them to do more good.Among the poor themselves, its effects would be still more important. That the principal and most permanent cause of poverty has little or no direct relation to forms of government, or the unequal division of property; and that, as the rich do not in reality possess the power of finding employment and maintenance for the poor, the poor cannot, in the nature of things, possess the right to demand them; are important truths flowing from the principle of population, which, when, properly explained, would by no means be above the most ordinary comprehensions. And it is evident that every man in the lower classes of society, who became acquainted with these truths, would be disposed to bear the distresses in which he might be involved with more patience; would feel less discontent and irritation at the government and the higher classes of society, on account of his poverty; would be on all occasions less disposed to insubordination and turbulence; and if he received assistance, either from any public institution or from the hand of private charity, he would receive it with more thankfulness, and more justly appreciate its value. (END)

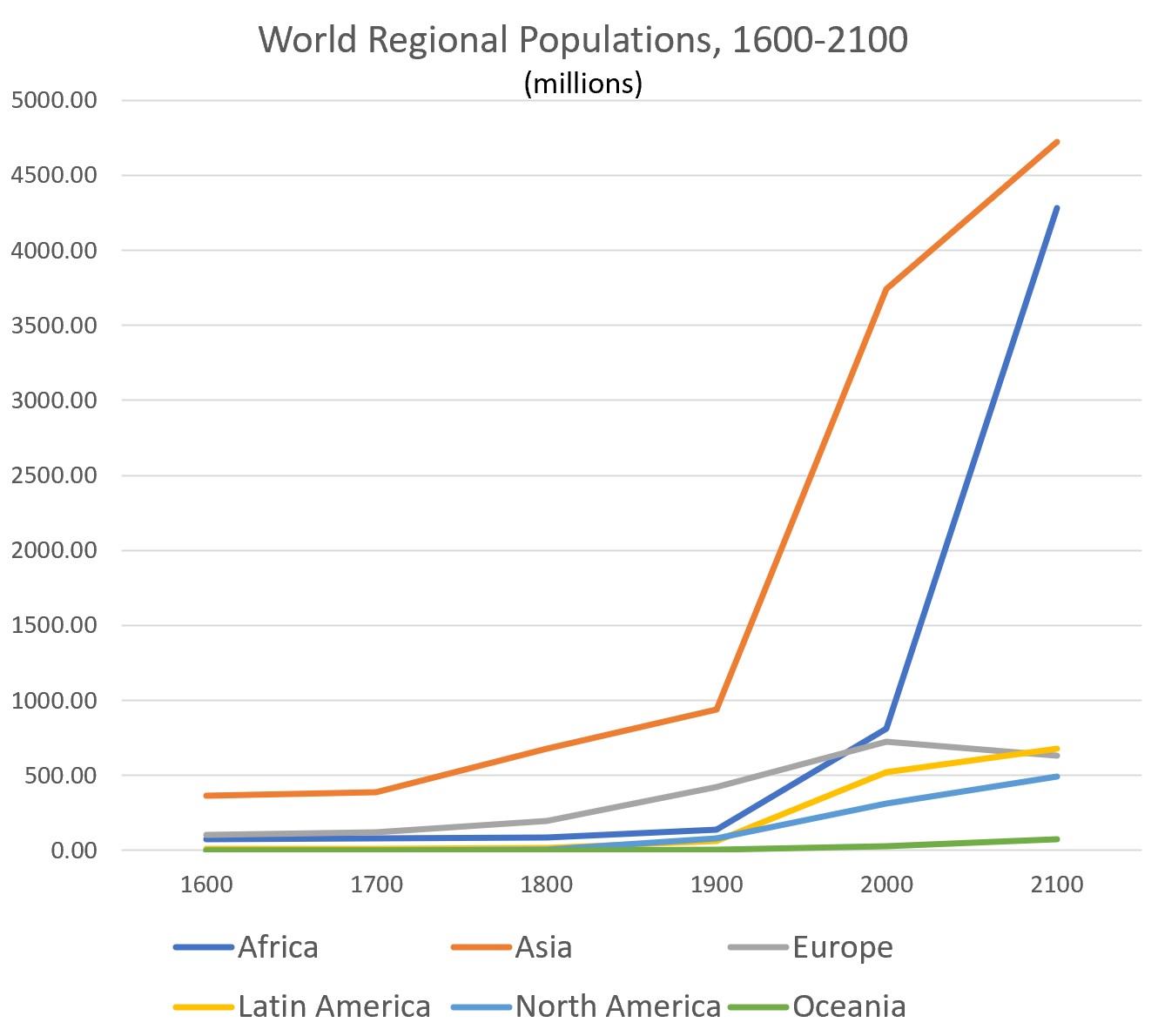

Analysis of the Population Reference Bureau Population: A Lively

Introduction, 4th Edition by Joseph A. McFalls Jr. For most of early human history, the death rate was about as high as the birth rate, and the rate of population growth was scarcely above zero. Significant population growth began about 8000 B.C., when humans began to farm and raise animals. By 1650, world population had expanded about 50 times—from 10 million to 500 million. Then world population shot up another 500 million people in just 150 years, reaching its first billion around 1800. It achieved its second billion by 1930, 130 years later; a third billion by 1960, only 30 years later; and a fourth billion by 1975, just 15 years later. But the last fifth and sixth billion (attained in 1987 and 1999), took just over a decade each. Although the pace of world population growth has slowed, we still expect another billion added before 2015. The unprecedented growth of world population in the modern era arose because births began to outnumber deaths. In ancient times, the birth rate and the death rate fluctuated around a relatively high level, and essentially cancelled each other out. This formed the first stage of a process described by the theory of the demographic transition. This theory evolved from the history of population growth in Europe and the United States and has been applied to populations everywhere.  In Stage 1 of the classic demographic transition, the death rate was extremely high because of poor health and harsh living conditions. Life expectancy at birth was less than 30 years. If birth rates had not also been high, societies would simply have died out—and many did! The cultures in these societies encouraged high birth rates through religious teachings and social pressure, essentially encouraging people to “be fruitful and multiply.” Socially, a man’s virility and a woman’s status often were linked to the number of children they had. But large families also served a practical function in these societies. Children furnished labor for family farms and supported elderly parents. Large families also increased the economic, political, and military power of their tribe or nation. Stage 2 of the demographic transition began when the death rate began to drop, probably because of improved living conditions and health practices. The birth rate remained high and may even have increased because women were healthier. The excess of births over deaths in the second stage of the transition ignited a population explosion. Why didn’t the birth rate fall in tandem with the death rate? Most societies eagerly accept technological and medical innovations, as well as other aspects of modernization, because of their obvious utility against the universal enemy: death. Social attitudes, such as the high value attached to having many children, are slower to change… In Stage 3 of the demographic transition, the birth rate moves downward, eventually catching up with the death rate. Population growth remains relatively high during the early part of the third stage, but falls to near zero in the later part. In Stage 4 of the demographic transition, the birth rate and the death rate are close together again, but they fluctuate around a relatively low level. More developed countries in Europe and elsewhere have completed the four stages of demographic transition. Most less developed nations are still in Stage 2 or the early part of Stage 3 of the transition. Excluding China, the growth rate for less developed countries was 1.9 percent in 2003. If growth were to continue at that rate, the population of these countries would double in less than 37 years. Will less developed countries eventually complete the demographic transition to low fertility and mortality? … |

Biography:

Biography: