|

David

Ricardo and the Corn Laws

Biograph

Ricardo

effectively makes two arguments for free trade - a dynamic one

and a static one. The dynamic one says that trade restriction,

over several years, will lead to slow economic growth, and

eventually a "stationary state." The static argument -

the principle of comparative advantage - says that free trade

is the most efficient policy in any single year, and is

mutually advantageous. Methodology:

On an invariable measure of value When commodities varied in relative value, it would be desirable to have the means of ascertaining which of them fell and which rose in real value, and this could be effected only by comparing them one after another with some invariable standard measure of value, which should itself be subject to none of the fluctuations to which other commodities are exposed. Of such a measure it is impossible to be possessed, because there is no commodity which is not itself exposed to the same variations as the things, the value of which is to be ascertained; that is, there is none which is not subject to require more or less labor for its production. . . To facilitate, then, the object of this enquiry, although I fully allow that money made of gold is subject to most of the variations of other things, I shall suppose it to be invariable, and therefore all alterations in price to be occasioned by some alteration in the value of the commodity of which I may be speaking.

On The

Principles of Political by David Ricardo, 1817 (third edition 1821) PREFACE

The produce of the earth - all that is derived from its

surface by the united application of labor, machinery, and

capital, is

divided among three

classes of the community; namely, the proprietor of the land,

the owner of the stock or capital necessary for its

cultivation, and the laborers by whose industry it is

cultivated. That this [labor theory of value] is really the foundation of the exchangeable value of all things, excepting those which cannot be increased by human industry, is a doctrine of the utmost importance in political economy; for from no source do so many errors, and so much difference of opinion in that science proceed, as from the vague ideas which are attached to the word value. If the quantity of labor realized in commodities, regulate their exchangeable value, every increase of the quantity of labor must augment the value of that commodity on which it is exercised, as every diminution must lower it... Section IVThe principle that the quantity of labor bestowed on the production of commodities regulates their relative value, considerably modified by the employment of machinery and other fixed and durable capital. In the former section we have supposed the implements and weapons necessary to kill the deer and salmon, to be equally durable, and to be the result of the same quantity of labor, and we have seen that the variations in the relative value of deer and salmon depended solely on the varying quantities of labor necessary to obtain them,—but in every state of society, the tools, implements, buildings, and machinery employed in different trades may be of various degrees of durability, and may require different portions of labor to produce them. The proportions, too, in which the capital that is to support labor, and the capital that is invested in tools, machinery and buildings, may be variously combined. This difference in the degree of durability of fixed capital, and this variety in the proportions in which the two sorts of capital may be combined, introduce another cause, besides the greater or less quantity of labor necessary to produce commodities, for the variations in their relative value—this cause is the rise or fall in the value of labor. Gardner Summary: Ricardo accepts the labor theory of value as a "close enough for abstract theory" explanation of relative prices, but acknowledges that it must be considered with several limitations and modifications:

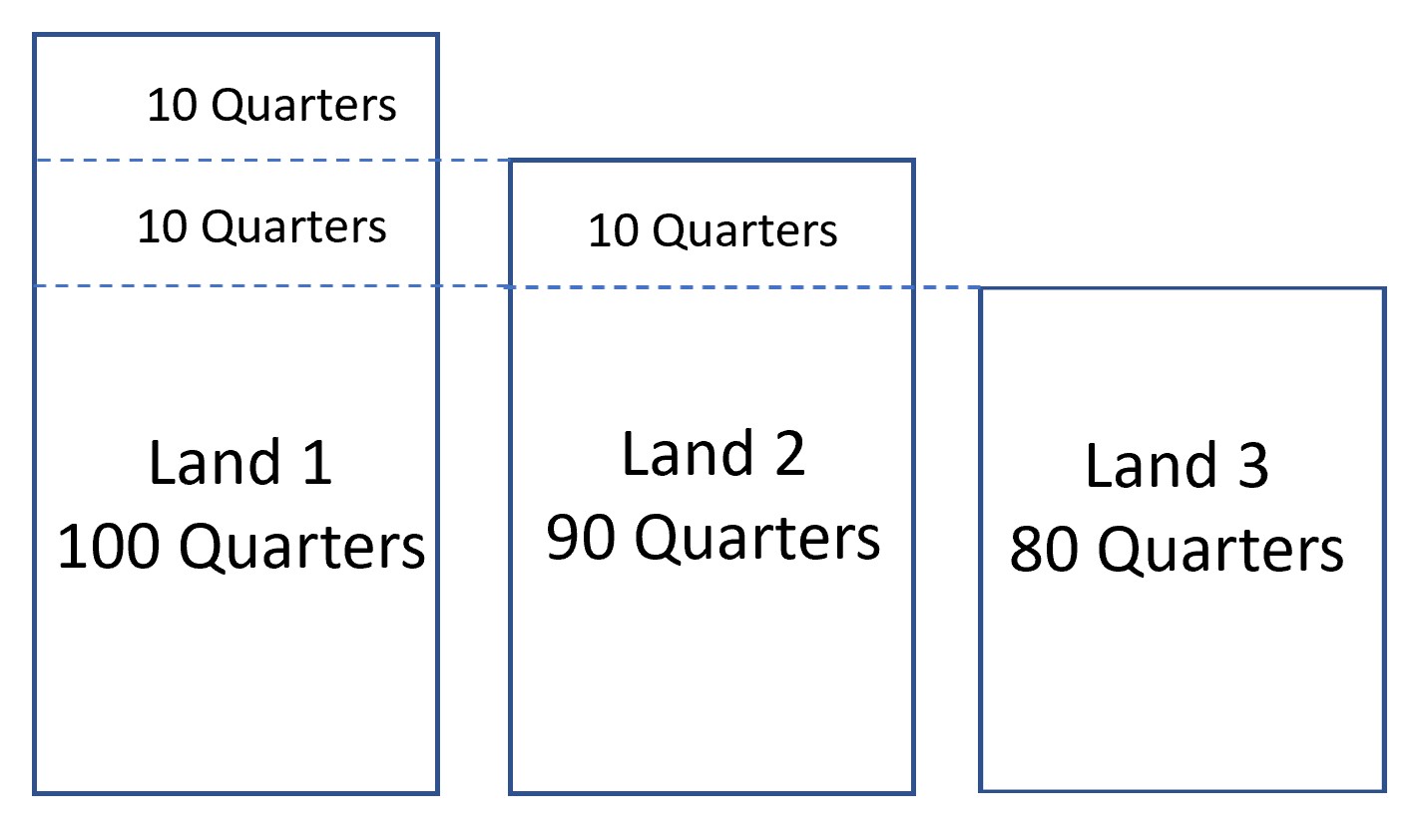

Chapter 2 On Rent Rent is that portion of

the produce of the earth, which is paid to the landlord for

the use of the original and indestructible powers of the soil. It is often,

however, confounded with the interest and profit of capital,

and, in popular language, the term is applied to whatever is

annually paid by a farmer to his landlord. . . .

It often, and, indeed, commonly happens, that before No. 2,

3, 4, or 5, or the inferior lands are cultivated, capital

can be employed more productively on those lands which are

already in cultivation. It may perhaps be found, that by

doubling the original capital employed on No. 1, though the

produce will not be doubled, will not be increased by 100

quarters, it may be increased by eighty-five quarters, and

that this quantity exceeds what could be obtained by

employing the same capital, on land No. 3. Chapter 5 Of Wages Labor,

like all other things which are purchased and sold, and

which may be increased or diminished in quantity, has its

natural and its market price. The natural price of labor is

that price which is necessary to enable the laborers, one

with another, to subsist and to perpetuate their race,

without either increase or diminution. On Profits The profits of stock, in different employments, having been shown to bear a proportion to each other, and to have a tendency to vary all in the same degree and in the same direction, it remains for us to consider what is the cause of the permanent variations in the rate of profit, and the consequent permanent alterations in the rate of interest.We have seen that the price of corn is regulated by the quantity of labor necessary to produce it, with that portion of capital which pays no rent. We have seen, too, that all manufactured commodities rise and fall in price, in proportion as more or less labor becomes necessary to their production. Neither the farmer who cultivates that quantity of land, which regulates price, nor the manufacturer, who manufactures goods, sacrifice any portion of the produce for rent. The whole value of their commodities is divided into two portions only: one constitutes the profits of stock, the other the wages of labor. . . . We have shown that in early stages of society, both the landlord's and the laborer's share of the value of the produce of the earth, would be but small; and that it would increase in proportion to the progress of wealth, and the difficulty of procuring food. We have shown, too, that although the value of the laborer's portion will be increased by the high value of food, his real share will be diminished; whilst that of the landlord will not only be raised in value, but will also be increased in quantity. The remaining quantity of the produce of the land, after the landlord and laborer are paid, necessarily belongs to the farmer, and constitutes the profits of his stock. But it may be alleged, that though as society advances, his proportion of the whole produce will be diminished, yet as it will rise in value, he, as well as the landlord and laborer, may, notwithstanding, receive a greater value... END Hypothetical Ricardian Example When

only Land 1 is used: Now, suppose the subsistence wage is 10 bushels of corn, valued at $10 If Farmer 1 hires 3 workers:

Now, if Land 1 and Land 2 are both used, the price of food is determined by production costs on Land 2 (half as fertile as Land 1).

On Land 2, in one week, one worker produces either:

The Theory of Comparative Advantage In the early 1950s, the mathematician/physicist, Stanislaw Ulam (a participant in the Manhattan Project that built the first nuclear weapons) challenged Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson to name one theory in all of the social sciences that is both true and nontrivial. Several years later, Samuelson responded with David Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage: "That it is logically true need not be argued before a mathematician; that is not trivial is attested by the thousands of important and intelligent men who have never been able to grasp the doctrine for themselves or to believe it after it was explained to them." The theory appears in Chapter 7, "On Foreign Trade," of Ricardo's Principles of Political Economy and Taxation: Under

a system of perfectly free commerce, each country naturally

devotes its capital and labor to such employments as are

most beneficial to each... It is this principle which

determines that wine shall be made in France and Portugal,

that corn shall be grown in America and Poland, and that

hardware and other goods shall be manufactured in England… If

Portugal had no commercial connection with other countries,

instead of employing a great part of her capital and

industry in the production of wines, with which she

purchases for her own use the cloth and hardware of other

countries, she would be obliged to devote a part of that

capital to the manufacture of those commodities, which she

would thus obtain probably inferior in quality as well as

quantity. The

quantity of wine which she shall give in exchange for the

cloth of England, is not determined by the respective

quantities of labor devoted to the production of each, as it

would be, if both commodities were manufactured in England,

or both in Portugal. England

may be so circumstanced, that to produce the cloth may

require the labor of 100 men for one year; and if she

attempted to make the wine, it might require the labor of

120 men for the same time. England would therefore find it

her interest to import wine, and to purchase it by the

exportation of cloth. To

produce the wine in Portugal, might require only the labor

of 80 men for one year, and to produce the cloth in the same

country, might require the labor of 90 men for the same

time. It would therefore be advantageous for her to export

wine in exchange for cloth. This

exchange might even take place, notwithstanding that the

commodity imported by Portugal could be produced there

with less labor than in England. Though she could

make the cloth with the labor of 90 men, she would import it

from a country where it required the labor of 100 men to

produce it, because it would be advantageous to her rather

to employ her capital in the production of wine, for which

she would obtain more cloth from England, than she could

produce by diverting a portion of her capital from the

cultivation of vines to the manufacture of cloth. Thus

England would give the produce of the labor of 100 men, for

the produce of the labor of 80. Such an exchange could not

take place between the individuals of the same country. The

labor of 100 Englishmen cannot be given for that of 80

Englishmen, but the produce of the labor of 100 Englishmen

may be given for the produce of the labor of 80 Portuguese,

60 Russians, or 120 East Indians. The difference in this

respect, between a single country and many, is easily

accounted for, by considering the difficulty with which

capital moves from one country to another, to seek a more

profitable employment, and the activity with which it

invariably passes from one province to another in the same

country. It

would undoubtedly be advantageous to the capitalists of

England, and to the consumers in both countries, that under

such circumstances, the wine and the cloth should both be

made in Portugal, and therefore that the capital and labour

of England employed in making cloth, should be removed to

Portugal for that purpose... Experience,

however, shews, that the fancied or real insecurity of

capital, when not under the immediate control of its owner,

together with the natural disinclination which every man has

to quit the country of his birth and connections, and

entrust himself with all his habits fixed, to a strange

government and new laws, check the emigration of capital. Gardner Comments: In Portugal, it takes 80 man-years to produce the wine that it exports But it would take 90 man-years to produce the cloth that it imports. So Portugal gets its cloth at a lower labor cost by importing it. So

Ricardo's formulation of comparative advantage was expressed

in term of the labor theory of value. In 1930, Gottfried

Haberler (who would leave Germany 6 years later to teach at

Harvard) reformulated the theory into its more modern

formulation, based on opportunity costs. Comparative Advantage Example:

Now, suppose after specialization, suppose that Brazil exports 10 tons of coffee and imports 9 tons of steel.

Conclusions: Ricardo's

theory suggests that there's almost always potential for

mutually-advantageous specialization and exchange between

two individuals or nations, and it pushes back against

BOTH the "cheap foreign labor" and "unequal exchange"

arguments for protectionism. On the other hand, it may seem

to suggests that an individual or country is unable to

change its comparative advantage, and should just accept its

fate in the current international division of labor. The

early history of the U.S. suggests that it's quite possible

for an agricultural country to develop competitive

advantages in manufacturing, technology, and services, and

China is making similar investments today. Trade theory and evidence: Gains of winners larger than losses of losers. Effects

on the poor. They lose from immobility, but gain from lower

prices. Changing U.S. attitudes toward foreign trade. Adam

Posen in Foreign Affairs, May/June 2021.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Background

Background