|

The Principles of Political Economy

by John Stuart Mill

Book 4

Chapter 6

Of the Stationary State

p. 124

It must

always have been seen, more or less distinctly, by political

economists, that the increase of wealth is not boundless: that

at the end of what they term the progressive state lies the

stationary state, that all progress in wealth is but a

postponement of this, and that each step in advance is an

approach to it. . . The richest and most prosperous countries

would very soon attain the stationary state, if no further

improvements were made in the productive arts, and if there

were a suspension of the overflow of capital from those

countries into the uncultivated or ill-cultivated regions of

the earth. . .

p. 126

2. I cannot, therefore, regard the

stationary state of capital and wealth with the unaffected

aversion so generally manifested towards it by political

economists of the old school. I am inclined to believe that it

would be, on the whole, a very considerable improvement on our

present condition. I confess I am not charmed with the ideal

of life held out by those who think that the normal state of

human beings is that of struggling to get on; that the

trampling, crushing, elbowing, and treading on each other's

heels, which form the existing type of social life, are the

most desirable lot of human kind, or anything but the

disagreeable symptoms of one of the phases of industrial

progress. . .

p. 127

. . . I know not why it should be matter of congratulation

that persons who are already richer than any one needs to be,

should have doubled their means of consuming things which give

little or no pleasure except as representative of wealth; or

that numbers of individuals should pass over, every year, from

the middle classes into a richer class, or from the class of

the occupied rich to that of the unoccupied. It

is only in the backward countries of the world that

increased production is still an important object: in those

most advanced, what is economically needed is a better

distribution, of which one indispensable means is a stricter

restraint on population.

p. 129

It is scarcely necessary to remark

that a stationary condition of

capital and population implies no stationary state of human

improvement. There would be as much scope as ever for

all kinds of mental culture, and moral and social progress; as

much room for improving the Art of Living, and much more

likelihood of its being improved, when minds ceased to be

engrossed by the art of getting on. Even the industrial arts

might be as earnestly and as successfully cultivated, with

this sole difference, that instead of serving no purpose but

the increase of wealth, industrial improvements would produce

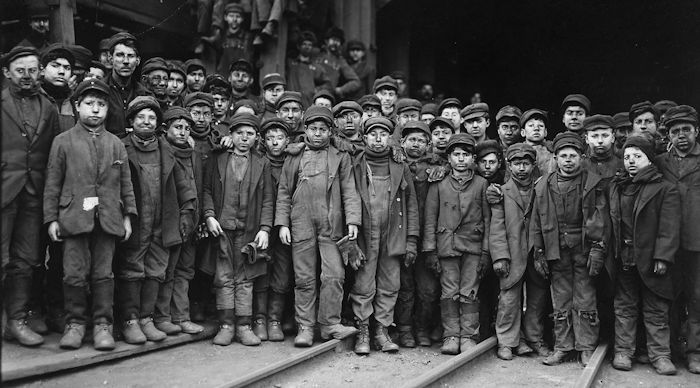

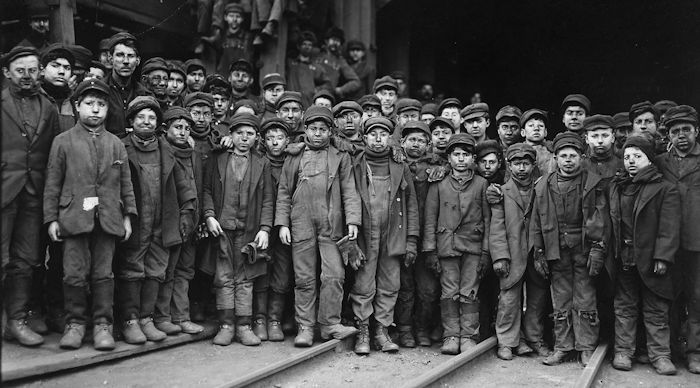

their legitimate effect, that of abridging labour. Hitherto it is questionable if all

the mechanical inventions yet made have lightened the day's

toil of any human being. They have enabled a greater

population to live the same life of drudgery and imprisonment,

and an increased number of manufacturers and others to make

fortunes. . .

Book 4

Chapter 7

On the Probable Futurity of

the Laboring Classes

p. 132

. . . The suggestions which have been promulgated . . .

have put in evidence the existence of two conflicting

theories, respecting the social position desirable for manual

labourers. The one may be called the theory

of dependence and protection, the other that of

self-dependence.

According to the former

theory, the lot of the poor, in all things which affect them

collectively, should be regulated for them, not by them.

They should not be required or encouraged to think for

themselves, or give to their own reflection or forecast an

influential voice in the determination of their destiny. It is

supposed to be the duty of the higher classes to think for

them, and to take the responsibility of their lot...

p. 132-33

All privileged and powerful classes, as such, have used their

power in the interest of their own selfishness, and have

indulged their self importance in despising, and not in

lovingly caring for, those who were, in their estimation,

degraded by being under the necessity of working for their

benefit. I do not affirm that what has always been must always

be, or that human improvement has no tendency to correct the

intensely selfish fillings engendered by power; but though the

evil may be lessened, it cannot be eradicated, until the power

itself is withdrawn. This, at least, seems to me undeniable,

that long before the superior classes could be sufficiently

improved to govern in the tutelary manner supposed, the

inferior classes would be too much improved to be so governed.

p. 136

2. It is on a far other basis that the

well-being and well-doing of the laboring people must

henceforth rest. The poor have

come out of leading strings, and cannot any longer be

governed or treated like children. To their own qualities

must now be commended the care of their destiny. . .

There is no reason to believe that prospect other than

hopeful. The progress indeed has hitherto been, and still is,

slow. But there is a spontaneous education going on in the

minds of the multitude... The instruction obtained from

newspapers and political tracts may not be the most solid kind

of instruction, but it is an immense improvement upon none at

all. . .

From this increase of intelligence, several effects may be

confidently anticipated. First: that they will become even

less willing than at present to be led and governed, and

directed into the way they should go, by the mere authority

and prestige of superiors. . .

p. 138

3. It appears to me impossible

but that the increase of intelligence, of

education, and of the love of independence among the working

classes, must be attended with a corresponding growth of the

good sense which manifests itself in provident habits of

conduct. . .

p. 142 There

can be little doubt that the status of hired labourers will

gradually tend to confine itself to the description of

work-people whose low moral qualities render them unfit for

anything more independent: and that the

relation of masters and work-people will be gradually

superseded by partnership, in one of two forms: in some

cases, association of the labourers with the capitalist; in

others, and perhaps finally in all, association of labourers

among themselves.

5. The first of these forms of association

has long been practiced, not indeed as a rule, but as an

exception... It is already a common practice to remunerate

those in whom peculiar trust is reposed, by means of a

percentage on the profits: and cases exist in which the

principle is, with excellent success, carried down to the

class of mere manual labourers. In the

American ships trading to China, it has long been the custom

for every sailor to have an interest in the profits of the

voyage; and to this has been ascribed the general good conduct

of those seamen, and the extreme rarity of any collision

between them and the government or people of the country.

p. 147 p. 147

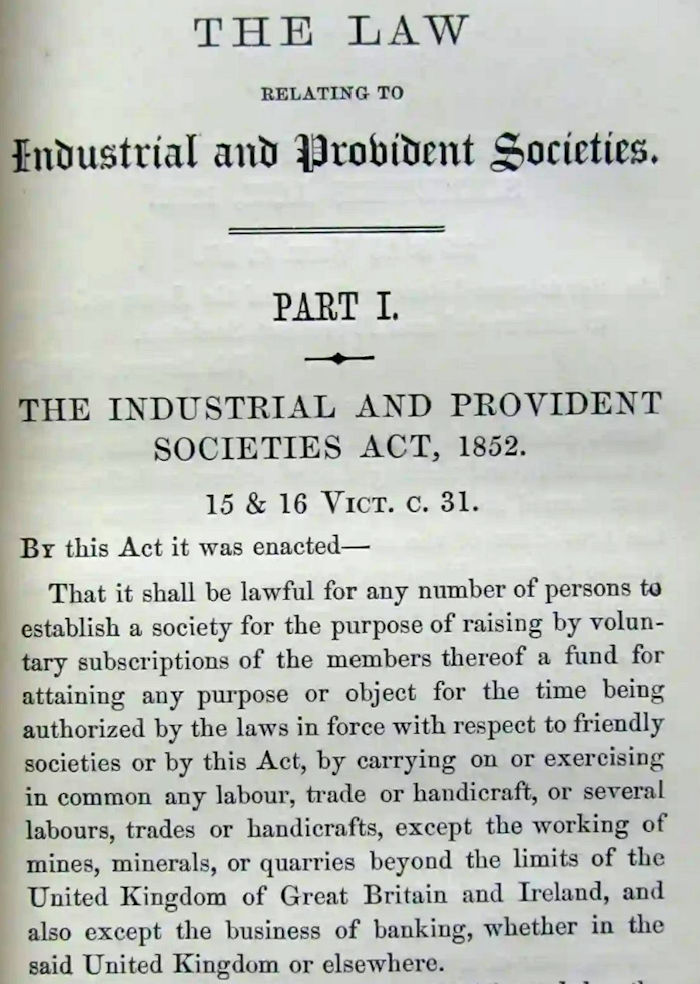

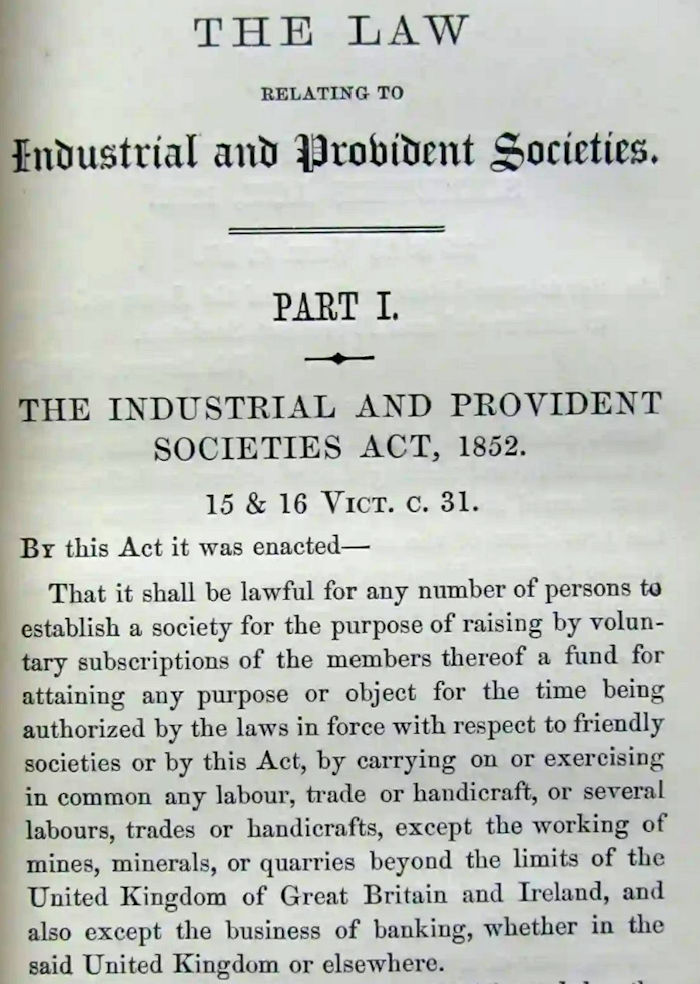

6. The form of association, however, which

if mankind continue to improve, must be expected in the end to

predominate, is not that which can exist between a capitalist

as chief, and work. people without a voice in the management,

but the association of the labourers themselves on terms of

equality, collectively owning the capital with which they

carry on their operations, and working under managers elected

and removable by themselves...

It is the

declared principle of most of these associations, that they do

not exist for the mere private benefit of the individual

members, but for the promotion of the co-operative cause. . .

When members quit the association, which they are always at

liberty to do, they carry none of the capital with them: it

remains an indivisible property, of which the members for the

time being have the use, but not the arbitrary disposal. . .

p. 156

7. I agree,

then with the Socialist writers in their conception

of the form which industrial operations tend to assume in the

advance of improvement; and I entirely share their opinion

that the time is ripe for commencing this transformation, and

that it should by all just and effectual means be aided and

encouraged. But while I agree and sympathize with Socialists

in this practical portion of their aims, I

utterly dissent from the most conspicuous and vehement part

of their teaching, their declamations against

competition. With moral conceptions in many respects far ahead

of the existing arrangements of society, they have in general

very confused and erroneous notions of its actual working; and

one of their greatest errors, as I conceive, is to charge upon

competition all the economical evils which at present exist. They forget that wherever

competition is not, monopoly is; and that monopoly, in all

its forms, is the taxation of the industrious for the

support of indolence, if not of plunder. . .

Book 5:

On The Influence of Government

Chapter 1

Of the Functions of

Government in General

p. 159

1. One of the most disputed questions both

in political science and in practical statesmanship at this

particular period, relates to the proper limits of the

functions and agency of governments. . . On the one hand,

impatient reformers, thinking it easier and shorter to get

possession of the government than of the intellects and

dispositions of the public, are under a constant temptation to

stretch the province of government beyond due bounds: while,

on the other, mankind have been so much accustomed by their

rulers to interference for purposes other than the public

good, or under an erroneous conception of what that good

requires, and so many rash proposals are made by sincere

lovers of improvement, for attempting, by compulsory

regulation, the attainment of objects which can only be

effectually or only usefully compassed by opinion and

discussion, that there has grown up a spirit of resistance in

limine to the interference of government, merely as such, and

a disposition to restrict its sphere of action within the

narrowest bounds. . .

p. 160

2. In attempting to enumerate the necessary

functions of government, we find them to be considerably more

multifarious than most people are at first aware of, and not

capable of being circumscribed by those very definite lines of

demarcation, which, in the inconsiderateness of popular

discussion, it is often attempted to draw round them. We

sometimes, for example, hear it said that governments ought to

confine themselves to affording protection against force and

fraud. . . .

Under which of these heads, the repression of force or of

fraud, are we to place the operation, for example, of the laws

of inheritance? Some such laws must exist in all societies. .

.

p. 164

There is a multitude of cases in

which governments, with general approbation, assume powers and

execute functions for which no reason can be assigned except

the simple one, that they conduce to general convenience. We

may take as an example, the function (which is a monopoly too)

of coining money. This is assumed for no more recondite

purpose than that of saving to individuals the trouble, delay,

and expense of weighing and assaying. No one, however, even of

those most jealous of state interference, has objected to this

as an improper exercise of the powers of government.

Prescribing a set of standard weights and measures is another

instance. Paving, lighting, and cleansing the streets and

thoroughfares, is another; whether done by the general

government, or as is more usual, and generally more advisable,

by a municipal authority. Making or improving harbors,

building lighthouses, making surveys in order to have accurate

maps and charts, raising dykes to keep the sea out, and

embankments to keep rivers in, are cases in point.

Examples might be indefinitely multiplied

without intruding on any disputed ground. But

enough has been said to show that the admitted functions of

government embrace a much wider field than can easily be

included within the ring-fence of any restrictive

definition, and that it is hardly possible to find any

ground of justification common to them all, except the

comprehensive one of general expediency; nor to limit the

interference of government by any universal rule, save the

simple and vague one, that it should never be admitted but

when the case of expediency is strong.

Book 5

Chapter 2

On the General Principles of

Taxation

p. 167

1. The qualities desirable, economically

speaking, in a system of taxation, have been embodied by Adam

Smith in four maxims or principles, which, having been

generally concurred by subsequent writers, may be said to have

become classical, and this chapter cannot be better commenced

than by quoting them.

'1. The subjects of every state ought to

contribute to the support of the government, as nearly as

possible in proportion to their respective abilities:

that is, in proportion to the revenue which they respectively

enjoy under the protection of the state. In the observation or

neglect of this maxim consists what is called the equality

or inequality of taxation.

'2. The tax which each individual is bound

to pay ought to be certain, and not arbitrary. . .

'3. Every tax ought to be levied at the

time, or in the manner, in which it is most likely to be

convenient for the contributor to pay it. . . Taxes upon such

consumable goods [are paid] little and little, as he has

occasion to buy the goods. . .

p. 168

'4. Every tax ought to be so contrived as

both to take out and to keep out of the pockets of the people

as little as possible over and above what it brings into the

public treasury of the state. . .

p. 169

The last three of these four maxims require little other

explanation or illustration than is contained in the passage

itself... But the first of the

four points, equality of taxation, requires to be more fully

examined, being a thing often imperfectly

understood...

Equality of taxation, therefore, as a maxim of politics, means

equality of sacrifice. It

means apportioning the contribution of each person towards the

expenses of government, so that he shall feel neither more nor

less inconvenience from his share of the payment than every

other person experiences from his. This standard, like other

standards of perfection, cannot be completely realized; but

the first object in every practical discussion should be to

know what perfection is.

There are persons, however,

who are not content with the general principles of justice as

a basis to ground a rule of finance upon, but must have

something, as they think, more specifically appropriate to the

subject. What best pleases them is, to regard the taxes paid

by each member of the community as an equivalent

for value received... If we wanted to estimate

the degrees of benefit which different persons derive from the

protection of government, we should have to consider who would

suffer most if that protection were withdrawn: to which

question if any answer could be made, it must be, that those

would suffer most who were weakest in mind or body, either by

nature or by position. Indeed, such persons would almost

infallibly be slaves. If there were any justice, therefore, in

the theory of justice now under consideration, those

who are least capable of helping or defending themselves,

being those to whom the protection of government is the most

indispensable, ought to pay the greatest share of its price:

the reverse of the true idea of distributive justice, which

consists not in imitating but in redressing the inequalities

and wrongs of nature.

p. 171

3. Setting out, then, from the maxim that

equal sacrifices ought to be demanded from all, we have next

to inquire whether this is in fact done, by making each

contribute the same percentage on his pecuniary means. Many persons maintain the

negative, saying that a tenth part taken from a small income

is a heavier burden than the same fraction deducted from one

much larger: and on this is grounded the very popular scheme

of what is called a graduated property tax, viz. an

income tax in which the percentage rises with the amount of

the income.

On the best consideration I am able to give to this question,

it appears to me that the portion of truth which the doctrine

contains, arises principally from the difference between a tax

which can be saved from luxuries, and one which trenches, in

ever so small a degree, upon the necessaries of life. . . The mode of adjusting these

inequalities of pressure, which seems to be the most

equitable, is that recommended by Bentham, of leaving a

certain minimum of income, sufficient to provide the

necessaries of life, untaxed. . . Each would then pay a

fixed proportion, not of his whole means, but of his

superfluities. . .

p. 173

The

exemption in favour of the smaller incomes should not, I

think, be stretched further than to the amount of income

needful for life, health, and immunity from bodily pain. . .

p. 174

Both in England and on the Continent

a graduated property tax has been advocated, on the avowed

ground that the state should use the instrument of taxation as

a means of mitigating the inequalities of wealth. I am as

desirous as any one, that means should be taken to diminish

those inequalities, but not so as to relieve the prodigal at

the expense of the prudent. To

tax the larger incomes at a higher percentage than the

smaller, is to lay a tax on industry and economy; to impose

a penalty on people for having worked harder and saved more

than their neighbors. It is not the fortunes which are

earned, but those which are unearned, that it is for the

public good to place under limitation. . . With respect to

the large fortunes acquired by gift or inheritance, the

power of bequeathing is one of those privileges of property

which are fit subjects for regulation on grounds of general

expediency; and I have already suggested, as a possible mode

of restraining the accumulation of large fortunes in the

hands of those who have not earned them by exertion, a

limitation of the amount which any one person should be

permitted to acquire by gift, bequest, or inheritance. Apart

from this, . . . I conceive that inheritances and legacies,

exceeding a certain amount, are highly proper subjects for

taxation: and that the revenue from them should be as great

as it can be made without giving rise to evasions, by

donation inter vivos or concealment of property,

such as it would be impossible adequately to check. The

principle of graduation (as it is called,) that is, of

levying a larger percentage on a larger sum, though its

application to general taxation would be in my opinion

objectionable, seems to me both just and expedient as

applied to legacy and inheritance duties.

p. 179

The principle, therefore, of equality

of taxation, interpreted in its only just sense, equality of

sacrifice, requires that a

person who has no means of providing for old age, or for

those in whom he is interested, except by saving from

income, should have the tax remitted on all that part of his

income which is really and bona fide applied to that

purpose.

If, indeed, reliance could be placed on the conscience of the

contributors, or sufficient security taken for the correctness

of their statements by collateral precautions, the

proper mode of assessing an income tax would be to tax only

the part of income devoted to expenditure, exempting that

which is saved. For when saved and invested (and all

savings, speaking generally, are invested) it thenceforth

pays income tax on the interest or profit which it brings,

notwithstanding that it has already been taxed on the

principal. Unless, therefore, savings are exempted from

income tax, the contributors are twice taxed on what they

save, and only once on what they spend.

p. 180

No

income tax is really just, from which savings are not

exempted; and no income tax ought to be voted without

that provision, if the form of the returns, and the nature of

the evidence required, could be so arranged as to prevent the

exemption from being taken fraudulent advantage of, by saving

with one hand and getting into debt with the other, or by

spending in the following year what had been passed tax-free

as saving in the year preceding. . .

Gardner

Summary of Mill on Taxation:

Objective and Rationale: To base

society on equality of opportunity and strong incentives

to work and save.

Income should be taxed at

a flat (not progressive) rate, but only after exemptions for

a base level of income needed for immediate subsistence and

for savings that are needed for subsistence in retirement.

On

the other hand, wealth acquired by gifts and inheritance

should be taxed at high and progressive levels (and, he says

elsewhere, at higher rates for more distant relatives),

limited only by the risk of causing excessive tax evasion.

So,

given that we need a certain amount of revenue to fund the

needs of government (domestic and national defense), raise

as much as possible from inheritance taxation, and then

raise the rest with income taxation, keeping the income tax

rate as low as possible, because he believed that income

taxes have a stronger negative influence on incentives and

productivity than inheritance taxes.

Book 5

Chapter 11

Of the Grounds and Limits of

the Laisser-faire or

Non-interference Principle

p. 324

1. We have now reached the last part of our

undertaking; the discussion, so far as suited to this treatise

(that is, so far as it is a question of principle, not detail)

of the limits of the province of government: the question, to

what objects governmental intervention in the affairs of

society may or should extend, over and above those which

necessarily appertain to it. . .

Without professing entirely to supply this deficiency of a

general theory, on a question which does not, as I conceive,

admit of any universal solution, I shall attempt to afford

some little aid towards the resolution of this class of

questions as they arise, by examining, in the most general

point of view in which the subject can be considered, what are

the advantages, and what the evils or inconveniences, of

government interference.

We must set out by distinguishing between two

kinds of intervention by the government, which,

though they may relate to the same subject, differ widely in

their nature and effects, and require, for their

justification, motives of a very different degree of urgency.

The intervention may extend to controlling the free agency of

individuals. Government may interdict all persons from doing

certain things; or from doing them without its authorization;

or may prescribe to them certain things to be done, or a

certain manner of doing things which it is left optional with

them to do or to abstain from. This is the authoritative interference of

government. There is another kind of intervention which is not

authoritative: when a government, instead of issuing a command

and enforcing it by penalties, adopts the course so seldom

resorted to by governments, and of which such important use

might be made, that of giving advice

and promulgating information; or when, leaving

individuals free to use their own means of pursuing any object

of general interest, the government, not meddling with them,

but not trusting the object solely to their care, establishes,

side by side with their arrangements, an agency of its own for

a like purpose. . .

2. It is evident, even at first sight, that the

authoritative form of government intervention has a much

more limited sphere of legitimate action than the other.

It requires a much stronger necessity to justify it in any

case . . .

p. 327

It is otherwise with governmental

interferences which do not restrain

individual free agency. When a government

provides means of fulfilling a certain end, leaving

individuals free to avail themselves of different means if in

their opinion preferable, there is no infringement of liberty,

no irksome or degrading restraint. One of the principal

objections to government interference is then absent. There

is, however, in almost all forms of government agency, one

thing which is compulsory. the provision of the pecuniary

means. These are derived from taxation...

p. 328

3. A second general objection to government

agency, is that every increase of the functions devolving on

the government is an increase

of its power, both in the form of authority, and

still more, in the indirect form of influence. . .

p. 329

4. A third general objection to government

agency, rests on the principle of the division

of labour. Every additional function undertaken by

the government, is a fresh occupation imposed upon a body

already overcharged with duties. . .

p. 331

5. But though a better organization of

governments would greatly diminish the force of the objection

to the mere multiplication of their duties, it would still

remain true that in all the more advanced communities, the

great majority of things are worse done by the intervention of

government, than the individuals most interested in the matter

would do them, or cause them to be done, if left to

themselves. The grounds of this truth are expressed with

tolerable exactness in the poplar dictum, that people

understand their own business and their own interests better,

and care for them more, than the government does, or can be

expected to do.

p. 332

6. I have reserved for the last place one

of the strongest of the reasons against the extension of

government agency, Even if the government could comprehend ...

all the most eminent intellectual capacity and active talent

of the nation, it would not be the less desirable that the

conduct of a large portion of the affairs of the society

should be left in the hands of the persons immediately

interested in them. The

business of life is an essential part of the practical

education of a people; without which, book and school

instruction, though most necessary and salutary, does not

suffice to qualify them for conduct, and for the adaptation

of means to ends.

p. 334

7. The preceding are the principal reasons,

of a general character, in favour of restricting to the

narrowest compass the intervention of a public authority in

the business of the community: and few will dispute the more

than sufficiency of these reasons, to throw, in every

instance, the burden of making

out a strong case, not on those who resist, but on those who

recommend, government interference. Laisser-faire,

in short, should be the general practice: every departure

from it, unless required by some great good, is a certain

evil.

p. 337

We have observed that, as

a general rule, the business of life is better performed

when those who have an immediate interest in it are

left to take their own course, uncontrolled either by the

mandate of the law or by the meddling of any public

functionary. The persons, or some of the persons, who do the

work, are likely to be better judges than the government, of

the means of attaining the particular end at which they aim.

p. 338

8. Now, the proposition that the consumer

is a competent judge of the commodity, can be admitted

only with numerous abatements and exceptions. He is

generally the best judge (though even this is not true

universally) of the material objects produced for his use.

These are destined to supply some physical want, or gratify

some taste or inclination. . . But there

are other things, of the worth of which the demand of the

market is by no means a test ... and the want of which is

least felt where the need is greatest. This is peculiarly

true of those things which are chiefly useful as tending to

raise the character of human beings. The uncultivated cannot

be competent judges of cultivation. Those who most

need to be made wiser and better, usually desire it least, and

if they desired it, would be incapable of finding the way to

it by their own lights. . .

p. 339 p. 339

With regard to elementary

education, the exception to ordinary rules may, I

conceive, justifiably be carried still further. There are

certain primary elements and means of knowledge, which it is

in the highest degree desirable that all human beings born

into the community should acquire during childhood. If their

parents, or those on whom they depend, have the power of

obtaining for them this instruction, and fail to do it, they

commit a double breach of duty, towards the children

themselves, and towards the members of the community

generally, who are all liable to suffer seriously from the

consequences of ignorance and want of education in their

fellow-citizens. It is

therefore an allowable exercise of the powers of government,

to impose on parents the legal obligation of giving

elementary instruction to children. This, however, cannot

fairly be done, without taking measures to insure that such

instruction shall be always accessible to them, either

gratuitously or at a trifling expense. . .

p. 341

One thing must be strenuously insisted on;

that the government must claim

no monopoly for its education, either in the lower or

in the higher branches; must exert neither authority nor

influence to induce the people to resort to its teachers in

preference to others, and must confer no peculiar advantages

on those who have been instructed by them. Though the government

teachers will probably be superior to the average of private

instructors, they will not embody all the knowledge

and sagacity to be found in all instructors taken together,

and it is desirable to leave open as many roads as possible to

the desired end. It is not endurable that a government should,

either de jure or de facto, have a complete

control over the education of the people. To

possess such a control, and actually exert it, is to be

despotic. . .

p. 342

The ground of the practical principle of

non-interference must here be, that most persons take a juster

and more intelligent view of their own interest, and of the

means of promoting it, than can either be prescribed to them

by a general enactment of the legislature, or pointed out in

the particular case by a public functionary. The maxim is

unquestionably sound as a general rule; but there is no

difficulty in perceiving some very large and conspicuous

exceptions to it. These may be classed under several heads.

First: -- The individual who is presumed to be the best judge

of his own interests may be incapable of judging or acting for

himself; may be a lunatic, an idiot, an

infant: or though not wholly incapable, may be of

immature years and judgment. In this case the foundation of

the laisser faire principle breaks down entirely.

p. 345

10. A second exception to the doctrine that

individuals are the best judges of their own interest, is when

an individual attempts to decide

irrevocably now, what will be best for his interest at some

future and distant time. . . The practical maxim of

leaving contracts free, is not applicable without great

limitations in case of engagement in perpetuity; and the law

should be extremely jealous of such engagements; should refuse

its sanction to them, when the obligations they impose are

such as the contracting party cannot be a competent judge of.

. . These considerations are eminently applicable to marriage,

the most important of all cases of engagement for life.

p. 346

11. The third exception ... has reference

to the great class of cases in which the individuals

can only manage the concern by delegated agency, and

in which the so-called private management is, in point of

fact, hardly better entitled to be called management by the

persons interested, than administration by a public officer.

Whatever, if left to spontaneous agency, can only be done by

joint-stock associations, will often be as well, and sometimes

better done, as far as the actual work is concerned, by the

state. . .

p. 349

There are many cases in which the agency, of whatever nature,

by which a service is performed, is certain, from the nature

of the case, to be virtually single; in which a practical

monopoly, with all the power it confers of taxing the

community, cannot be prevented from existing. I have already

more than once adverted to the case of the gas and water

companies, among which, though perfect freedom is allowed to

competition, none really takes place, and practically they are

found to be even more irresponsible, and unapproachable by

individual complaints, than the government...

p. 349

12. To a fourth case of exception I must

request particular attention, it being one to which as it

appears to me, the attention of political economists has not

yet been sufficiently drawn. There are matters in which the

interference of law is required, not to overrule the judgment

of individuals respecting their own interest, but to

give effect to that judgment:

they being unable to give effect to it except by concert,

which concert again cannot be effectual unless it receives

validity and sanction from the law. (Gardner:

Maybe requiring pharmacies to post their prices?)

p. 353

13. Fifthly; the argument against

government interference ... cannot apply to the very large

class of cases, in which those acts of individuals with which

the government claims to interfere, are not done by those

individuals for their own interest, but for the interest of

other people. This includes, among other things, the important

and much agitated subject of public

charity.

p. 355

In so far as the subject admits of any general doctrine or

maxim, it would appear to be this -- that if assistance is

given in such a manner that the condition of the person helped

is as desirable as that of the person who succeeds in doing

the same thing without help, the assistance, if capable of

being previously calculated on, is mischievous: but if, while

available to everybody, it leaves to every one a strong motive

to do without it if he can, it is then for the most part

beneficial. . . But if, consistently with guaranteeing

all persons against absolute want, the condition of those

who are supported by legal charity can be kept considerably

less desirable than the condition of those who find support

for themselves, none but beneficial consequences can

arise from a law which renders it impossible for any person,

except by his own choice, to die from insufficiency of food. .

.

Subject to these conditions, I conceive it

to be highly desirable, that the

certainty of subsistence should be held out by law to the

destitute able-bodied, rather than that their relief should

depend on voluntary charity. In the first place,

charity almost always does too much or too little: it lavishes

its bounty in one place, and leaves people to starve in

another. Secondly, since the state must necessarily provide

subsistence for the criminal poor while undergoing punishment,

not to do the same for the poor who have not offended is to

give a premium on crime. And lastly, if the poor are left to

individual charity, a vast amount of mendacity is inevitable.

What the state may and should abandon to private charity, is

the task of distinguishing between one case of real necessity

and another. Private charity can give more to the more

deserving. The state must act by general rules. It cannot

undertake to discriminate between the deserving and the

undeserving indigent. It owes no more than subsistence to the

first, and can give no less to the last. . . Private

charity can make these distinctions; and in bestowing its own

money, is entitled to do so according to its own judgment. . .

p. 366

16. The preceding heads comprise, to the

best of my judgment, the whole of the exceptions to the

practical maxim, that the business of society can be best

performed by private and voluntary agency. It is, however,

necessary to add, that the intervention of government cannot

always practically stop short at the limit which defines the

cases intrinsically suitable for it. In the particular

circumstances of a given age or nation, there

is scarcely anything really important to the general

interest, which it may not be desirable, or even necessary,

that the government should take upon itself, not because

private individuals cannot effectually perform it, but

because they will not. At some times and places,

there will be no roads, docks, harbors, canals, works of

irrigation, hospitals, schools, colleges, printing-presses,

unless the government establishes them; the public being

either too poor to command the necessary resources, or too

little advanced in intelligence to appreciate the ends, or not

sufficiently practised in joint action to be capable of the

means...

Gardner

Summary on Public Charity:

Protect all from "absolute want,"

but do it in a way that preserves incentives - a person will

always benefit from working if they are able. Basic

subsistence needs should be guaranteed by the state, based

on objective criteria, and should NOT go only to the

"deserving" poor, because the state also provides

subsistence to prisoners. Private charities can give

additional support to the "deserving" poor.

|

p. 147

p. 147

p. 339

p. 339