|

Alfred

Marshall Biography

1843

- Born in Bermondsey, a district of southeast London near

Tower Bridge. Had his early education with his father, who

wanted him to attend Oxford and study religion for the

ministry, but instead he went to Cambridge to study math

(Buchholz wonders whether that rebellion subconsciously caused

him to place his math in footnotes).

1865

- Graduated in math and developed an interest in philosophy,

and that led him to moral philosophy - Economics

1885

- Appointed professor of political economy at Cambridge, where

he established a more rigorous curriculum and trained a

generation of economists, including J.M. Keynes and A.C.

Pigou, and remained until his retirement in 1908.

1890

- Published Principles of Economics, which became,

arguably, the most successful textbook before Paul Samuelson's

book with the same name after World War II.

1924

- Died in Cambridge.

Belief

about the use of math in economics (written in a letter to a

friend).

"(1)

Use mathematics as shorthand language, rather than as an

engine of inquiry. (2) Keep to them till you have done. (3)

Translate into English. (4) Then illustrate by examples that

are important in real life (5) Burn the mathematics. (6) If

you can't succeed in 4, burn 3. This I do often."

Principles

of Economics:

An Introductory Volume

by Alfred Marshall

1890

Preface to the First Edition

...[E]thical

forces are among those of which the economist has to take

account. Attempts have indeed been made to construct an

abstract science with regard to the actions of an “economic

man,” who is under no ethical influences and who pursues

pecuniary gain warily and energetically, but mechanically and

selfishly. But they have not been successful, nor even

thoroughly carried out. For they have never really treated the

economic man as perfectly selfish: no one could be relied on

better to endure toil and sacrifice with the unselfish desire

to make provision for his family; and his normal motives have

always been tacitly assumed to include the family affections.

But if they include these, why should they not include all

other altruistic motives the action of which is so far uniform

in any class at any time and place, that it can be reduced to

general rule? There seems to be no reason; and in the present

book normal action is taken to be that which may be expected,

under certain conditions, from the members of an industrial

group; and no attempt is made to exclude the influence of any

motives, the action of which is regular, merely because they

are altruistic. If the book has any special character of its

own, that may perhaps be said to lie in the prominence which

it gives to this and other applications of the Principle of

Continuity...

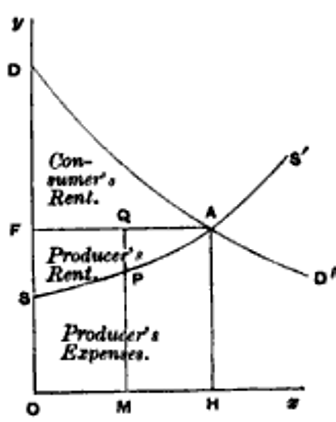

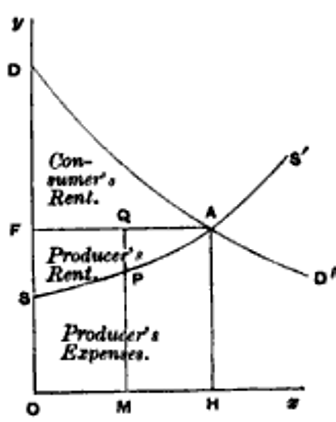

Under

the guidance of Cournot, and in a less degree of von Thünen, I

was led to attach great importance to the fact that our

observations of nature, in the moral as in the physical world,

relate not so much to aggregate quantities, as to increments

of quantities, and that in particular the demand for a thing

is a continuous function, of which the “marginal" increment

is, in stable equilibrium, balanced against the corresponding

increment of its cost of production. It is not easy to get a

clear full view of continuity in this aspect without the aid

either of mathematical symbols or of diagrams. The use of the

latter requires no special knowledge, and they often express

the conditions of economic life more accurately, as well as

more easily, than do mathematical symbols; and therefore they

have been applied as supplementary illustrations in the

footnotes of the present volume. .

BOOK I

Chapter 1

Introduction

p. 1a

1. Political economy or economics is a study of mankind in the

ordinary business of life;

it examines that part of individual and social action which is

most closely connected with the attainment and with the use of

the material requisites of wellbeing. . .

p. 2c

[T]here are vast numbers of people both in

town and country who are brought up with insufficient food,

clothing, and house-room; whose education is broken off early

in order that they may go to work for wages; who thenceforth

are engaged during long hours in exhausting toil with

imperfectly nourished bodies, and have therefore no chance of

developing their higher mental faculties. Their life is not

necessarily unhealthy or unhappy. Rejoicing in their

affections towards God and man, and perhaps even possessing

some natural refinement of feeling, they

may lead lives that are

far less incomplete than those of many, who have more

material wealth. But, for all that, their poverty is

a great and almost unmixed evil to them. Even when they are

well, their weariness often

amounts to pain, while their pleasures are few; and

when sickness comes,

the suffering caused by poverty increases tenfold. . .

p. 3b

2. Slavery

was regarded by Aristotle as an ordinance

of nature, and so probably was it by the slaves

themselves in olden time. The dignity of man was proclaimed by

the Christian religion: it has been asserted with increasing

vehemence during the last hundred years: but, only through the

spread of education during quite recent times, are we

beginning to feel the full import of the phrase. Now

at last we are setting ourselves seriously to inquire whether

it is necessary that there should

be any so-called "lower classes" at all . . .

The hope

that poverty and ignorance may gradually be extinguished,

derives indeed much support from the steady progress of the

working classes during the nineteenth century. The steam-engine

has relieved them of much exhausting and degrading toil; wages

have risen; education

has been improved and become more general; the railway

and the printing-press have enabled members of the

same trade in different parts of the country to communicate

easily with one another, and to undertake and carry out broad

and far-seeing lines of policy . . .

p. 13a

Intermediate between these two extremes are

the great body of economists who, working on parallel lines in

many different countries, are bringing to their studies an

unbiassed desire to ascertain the truth, and a willingness to

go through with the long and heavy work by which alone

scientific results of any value can be obtained. Varieties of

mind, of temper, of training and of opportunities lead them to

work in different ways, and to give their chief attention to

different parts of the problem. All are bound more or less to

collect and arrange facts and

statistics relating to past and present times; and

all are bound to occupy themselves more or less with analysis

and reasoning on the basis of those facts

which are ready at hand: but some find the former task the

more attractive and absorbing, and others the latter. This division of labour, however,

implies not opposition, but harmony of purpose. The

work of all adds something or other to that knowledge, which

enables us to understand the influences exerted on the quality

and tone of man's life by the manner in which he earns his

livelihood, and by the character of that livelihood.

Book I

Chapter 4

The Order and Aims of Economic

Studies

p. 38b

Economic laws are statements with regard to

the tendencies of

man's action under certain

conditions. They are hypothetical only in the same

sense as are the laws of the physical sciences: for those laws

also contain or imply conditions. But there is more difficulty

in making the conditions clear, and more danger in any failure

to do so, in economics than in physics. The laws of human

action are not indeed as simple, as definite or as clearly

ascertainable as the law of gravitation; but many of them may

rank with the laws of those natural sciences which deal with

complex subject-matter. . .

p. 41b

The following

problems seem to be of special urgency now in our own country.

--

How should we act so as to increase

the good and diminish the evil influences of economic

freedom, both in its ultimate results and in the

course of its progress? If the first are good and the latter

evil, but those who suffer the evil, do not reap the good; how

far is it right that they should suffer for the benefit of

others?

Taking it for granted that a more

equal distribution of wealth is to be desired, how far would this justify

changes in the institutions of property, or

limitations of free enterprise even when they would be likely

to diminish the aggregate of wealth? . . .

Ought we to rest content with the existing

forms of division of labour? Is it necessary that

large numbers of the people should be exclusively occupied

with work that has no

elevating character? Is it possible to educate

gradually among the great mass of workers a new capacity for

the higher kinds of work; and in particular for undertaking

co-operatively the management of the business in which they

are themselves employed?

What are the proper relations of individual

and collective action in a stage of civilization such as ours?

How far ought voluntary association in its various forms, old

and new, to be left to supply collective action for those

purposes for which such action has special advantages? What business affairs should be

undertaken by society itself acting through its government,

imperial or local? Have we, for instance, carried as

far as we should the plan of collective ownership and use of

open spaces, of works of

art, of the means of instruction and amusement, as

well as of those material requisites of a civilized life, the

supply of which requires united action, such as gas and water,

and railways?

When government does not itself directly

intervene, how far should it allow individuals and

corporations to conduct their own affairs as they please? How

far should it regulate

the management of railways and other concerns which are to

some extent in a position of monopoly, and again of land and

other things the quantity of which cannot be increased by man?

. . .

Are the prevailing methods of using wealth

entirely justifiable? What scope is there for the moral

pressure of social opinion in constraining and directing

individual action in those economic relations in which the

rigidity and violence of government interference would be

likely to do more harm than good? In what respect do the duties of one nation to another

in economic matters differ from those of members of the same

nation to one another?

P. 43c

The natural

sciences and especially the physical group of them

have this great advantage as a discipline over all studies of

man's action, that in them the investigator is called on for exact conclusions which

can be verified by subsequent observation or experiment. . .

In

sciences that relate to man exactness is less attainable.

. . The scientific student of history is hampered by his

inability to experiment and even more by the absence of any

objective standard to which his estimates of relative

proportion can be referred. . . The economist also is hampered

by this difficulty, but in a less degree than other students

of man's action; for indeed he has some share in those

advantages which give precision and objectivity to the work of

the physicist. . .

p. 44c

In smaller matters, indeed, simple experience will suggest the

unseen. . . But greater effort, a larger range of view, a more

powerful exercise of the imagination are needed in tracking

the true results of, for instance, many plausible schemes for

increasing steadiness of employment. For that purpose it is

necessary to have learnt

how closely connected are changes in credit, in domestic

trade, in foreign trade competition, in harvests, in prices;

and how all of these affect steadiness of employment for good

and for evil. It is necessary to watch how

almost every considerable economic event in any part of the

Western world affects employment in some trades at least in

almost every other part. If we deal only with those causes of unemployment

which are near at hand,

we are likely to make no

good cure of the evils we see; and we are likely to

cause evils, that we do not see. And if we are to look for

those which are far off and weigh them in the balance, then

the work before us is a high discipline for the mind.

p. 47a

Some harsh employers and politicians, defending exclusive

class privileges early in last century, found it convenient to

claim the authority of political economy on their side; and

they often spoke of themselves as "economists." And even in

our own time, that title has been assumed by opponents of

generous expenditure on the education of the masses of the

people, in spite of the fact that living economists with one

consent maintain that such expenditure is a true economy, and

that to refuse it is both wrong and bad business from a

national point of view. But Carlyle and Ruskin, followed by

many other writers who had no part in their brilliant and

ennobling poetical visions, have without examination held the

great economists responsible for sayings and deeds to which

they were really averse; and in consequence there has grown up

a popular misconception of their thoughts and character.

The fact is that nearly

all the founders of modern economics were men of gentle and

sympathetic temper, touched with the enthusiasm of humanity.

They cared little for wealth for themselves; they cared much

for its wide diffusion among the masses of the people. They

opposed antisocial monopolies however powerful. In their

several generations they supported the movement against the

class legislation which denied to trade unions privileges that

were open to associations of employers; or they worked for a

remedy against the poison which the old Poor Law was

instilling into the hearts and homes of the agricultural and

other labourers; or they supported the factory acts, in spite

of the strenuous opposition of some politicians and employers

who claimed to speak in their name. They were without

exception devoted to the doctrine that the wellbeing of the

whole people should be the ultimate goal of all private effort

and all public policy. But they were strong in courage and

caution; they appeared cold,

because they would not assume the responsibility of

advocating rapid advances on untried paths, for the

safety of which the only guarantees offered were the confident

hopes of men whose imaginations were eager, but not steadied

by knowledge nor disciplined by hard thought.

Their

caution was perhaps a little greater than necessary:

for the range of vision even of the great seers of that age

was in some respects narrower than is that of most educated

men in the present time; when, partly through the suggestions

of biological study, the influence of circumstances in

fashioning character is generally recognized as the dominant

fact in social science. Economists

have accordingly now learnt to take a larger and more

hopeful view of the possibilities of human progress. They

have learnt to trust that the human will, guided by careful

thought, can so modify circumstances as largely to modify

character; and thus to bring about new conditions of life

still more favourable to character; and therefore to

the economic, as well as the moral, wellbeing of the masses of

the people. Now as ever it is their duty to oppose all

plausible short cuts to that great end, which would sap the

springs of energy and initiative.

The rights

of property, as such,

have not been venerated by those master minds who

have built up economic science; but the authority of the

science has been wrongly assumed: by some who have pushed the

claims of vested rights to extreme and antisocial uses. It may

be well therefore to note that the tendency of careful

economic study is to base

the rights of private property not on any abstract

principle, but on the observation that in the past they have

been inseparable from solid progress; and that

therefore it is the part of responsible men to proceed

cautiously and tentatively in abrogating or modifying even

such rights as may seem to be inappropriate to the ideal

conditions of social life.

Book II

Chapter 3

Production, Consumption, Labor,

Necessaries

p. 63a

1. Man cannot create

material things. In the mental and moral world indeed he may

produce new ideas; but when he is said to produce material

things, he really only produces utilities; . . .

It is

sometimes said that traders do not produce: that

while the cabinet-maker produces furniture, the furniture

dealer merely sells what is already produced. But there is no scientific foundation for this

distinction. They

both produce utilities, and neither of them can do more:

the furniture-dealer moves and rearranges matter so as to make

it more serviceable than it was before, and the carpenter does

nothing more.

Gardner

Note: Starting, at least, with Aristotle and Plato,

and following through Adam Smith and Karl Marx, there had

been the idea that people who produced services were somehow

less productive than those who produced physical goods, and

that bias was reflected in the national income accounts of

the Soviet Union and other countries it influenced. Here,

Marshall give the basic argument that all workers produce

utility/value, and thus GDP is the final value of all goods

and SERVICES produced in a year.

Book III

Chapter 3

Gradations of Consumers' Demand

p. 93a

There is an endless variety of wants, but

there is a limit to each separate want. This familiar and

fundamental tendency of human nature may be stated in the law of satiable wants or of

diminishing utility thus:-The total utility of a

thing to anyone (that is, the total pleasure or other benefit

it yields him) increases with every increase in his stock of

it, but not as fast as his stock increases. If his stock of it

increases at a uniform rate the benefit derived from it

increases at a diminishing rate. In other words, the additional

benefit which a person derives from a given increase of his

stock of a thing, diminishes with every increase in the

stock that he already has. . .

p. 94a

There is however an implicit

condition in this law which should be made clear. It

is that we do not suppose

time to be allowed for any alteration in the character or

tastes of the man himself. It is therefore no

exception to the law that the more good music a man hears, the

stronger is his taste for it likely to become; . . .

p. 94b

2. Now let us translate this

law of diminishing utility into terms of price. Let

us take an illustration from the case of a commodity such as tea, which is in constant

demand and which can be purchased in small quantities.

Suppose, for instance, that tea of a certain quality is to be

had at 2s. per lb. A person might be willing to give 10s. for

a single pound once a year rather than go without it

altogether; while if he could have any amount of it for

nothing he would perhaps not care to use more than 30 lbs. in

the year. But as it is, he buys perhaps 10 lbs. in the year;

that is to say, the difference between the satisfaction which

he gets from buying 9 lbs. and I 0 lbs. is enough for him to

be willing to pay 2s. for it: while the fact that he does not

buy an eleventh pound, shows that he does not think that it

would be worth an extra 2s. to him. That is, 2s.

a pound measures the utility to him of the tea which lies at

the margin or terminus or end of his purchases; it measures

the marginal utility to him. If the price which he is

just willing to pay for any pound be called his demand price,

then 2s. is his marginal demand price. And our law may be

worded:-

The larger the amount of a thing that a

person has the less, other things being equal (i.e. the

purchasing power of money, and the amount of money at his

command being equal), will be the price which he will pay for

a little more of it: or in other words his marginal demand

price for it diminishes.

His demand becomes efficient, only when the

price which he is willing to offer reaches that at which

others are willing to sell.

This last sentence reminds us that we

have as yet taken no account of changes in the marginal

utility of money, or general purchasing power. At one

and the same time, a person's material resources being

unchanged, the marginal

utility of money to him is a fixed quantity, so that the

prices he is just willing to pay for two commodities are to

one another in the same ratio as the utility of those two

commodities.

p. 96b

4. To obtain complete

knowledge of demand for anything, we should have to

ascertain how much of it he

would be willing to purchase at each of the prices at

which it is likely to be offered; and the circumstance of his

demand for, say, tea can be best expressed by a list of the

prices which he is willing to pay; . . .

p. 97a

When we say that a person's demand for

anything increases, we mean that he will buy more of it than

he would before at the same price, and that he will buy as

much of it as before at a higher price. A

general increase in his demand is an increase throughout the

whole list of prices at which he is willing to purchase

different amounts of it, and not merely that he is

willing to buy more of it at the current prices.

p. 99a

The total demand in the place for, say, tea, is the sum of the

demands of all the individuals there. Some will be richer and

some poorer than the individual consumer whose demand we have

just written down; some will have a greater and others a

smaller liking for tea than he has. Let us suppose that there

are in the place a million purchasers of tea, and that their

average consumption is equal to his at each several price. . .

There is then one

general law of demand: -The greater the amount to be

sold, the smaller must be the price at which it is offered in

order that it may find purchasers; or, in other words, the

amount demanded increases with a fall in price, and diminishes

with a rise in price. . .

BOOK III

Chapter 4

The Elasticity of Wants

p. 102c

The elasticity (or responsiveness) of

demand in a market is great or small according as the amount

demanded increases much or little for a given fall in price,

and diminishes much or little for a given rise in price.

2. The price which is so high relatively to

the poor man as to be almost prohibitive, may be scarcely felt

by the rich; the poor man, for instance, never tastes wine,

but the very rich man may drink as much of it as he has a

fancy for, without giving himself a thought of its cost. We

shall therefore get the

clearest notion of the law of the elasticity of demand by

considering one class of society at a time. . .

When the price of a thing is very high

relatively to any class, they will buy but little of it; and

in some cases custom and habit may prevent them from using it

freely even after its price has fallen a good deal. . . The

elasticity of demand is great for high prices, and great, or

at least considerable, for medium prices; but it declines as

the price falls; and gradually fades away if the fall goes so

far that satiety level is reached.

p. 105a

3. There are some things the current prices

of which in this country are very low relatively even to the

poorer classes; such are for instance salt, and many kinds of

savours and flavours, and also cheap medicines. It is doubtful

whether any fall in price would induce a considerable increase

in the consumption of these.

p. 106b

4. The case of necessaries is exceptional. When the price of

wheat is very high, and again when it is very low, the demand

has very little elasticity: at all events if we assume that

wheat, even when scarce, is the cheapest food for man; and

that, even when most plentiful, it is not consumed in any

other way.

p. 107c

The demand for things of a higher quality

depends much on sensibility. some people care little for a

refined flavour in their wine provided they can get plenty of

it: others crave a high quality, but are easily satiated. . .

The effective demand for first-rate music is elastic only in

large towns; for second-rate music it is elastic both in large

and small towns.

P. 110

6. Next, allowance must be made for changes

in fashion, and taste and habit, for the opening out of new

uses of a commodity, for the discovery

or improvement or cheapening of other things that can

be applied to the same uses with it. In all these cases there

is great difficulty in allowing for the time that elapses

between the economic cause and its effect. For time is

required to enable a rise in the price of a commodity to exert

its full influence on consumption. Time is required for

consumers to become familiar

with substitutes that can be used instead of it, and

perhaps for producers to get into the habit of producing them

in sufficient quantities. Time may be also wanted for the growth of habits of familiarity

with the new commodities and the

discovery of methods of economizing them.

For instance when

wood and charcoal became dear in England, familiarity with

coal as a fuel grew slowly, fireplaces were but

slowly adapted to its use, and an organized traffic in it did

not spring up quickly even to places to which it could be

easily carried by water. The invention of processes by which

it could be used as a substitute for charcoal in manufacture

went even more slowly, and is indeed hardly yet complete. . .

p. 111b

Another difficulty of the same kind arises from the fact that

there are many purchases

which can easily be put off for a short time, but not for a

long time. This is often the case with regard to

clothes and other things which are worn out gradually, and

which can be made to serve a little longer than usual under

the pressure of high prices.

BOOK III

Chapter 6

Value and Utility

p. 124a

1. We may now turn to consider how far the price which is

actually paid for a thing represents the benefit that arises

from its possession. This is a wide subject on which economic

science has very little to say, but that little is of some

importance.

We have already seen that the

price which a person pays for a thing can never exceed, and

seldom comes up to that which he would be willing to pay

rather than go without it: so that the satisfaction

which he gets from its purchase generally exceeds

that which he gives up in paying away its price; and

he thus derives from the purchase a surplus of satisfaction.

The excess of the price which he would be willing to pay

rather than go without the thing, over that which he actually

does pay, is the economic measure

of this surplus satisfaction. It may

be called consumer's surplus.

It is obvious that the consumer's surpluses

derived from some commodities are much greater than from

others. There are many comforts and

luxuries of which the prices are very much below those which

many people would pay rather than go entirely without them;

and which therefore afford a very great consumer's surplus.

Good instances are matches, salt, a penny newspaper, or a

postage-stamp. . .

2. In order to give definiteness to our

notions, let us consider the case of tea purchased for

domestic consumption. Let us take the case of a man, who, if

the price of tea were 20s. a pound, would just be induced to

buy one pound annually; who would just be induced to buy two

pounds if the price were 14s., three pounds if the price were

10s., four pounds if the price were 6s., five pounds if the price were 4s., six pounds

if the price were 3s., and who, the price being actually 2s.,

does purchase seven pounds. We have to investigate the

consumer's surplus which he deri ves from

his power of purchasing tea at 2s. a pound. . . ves from

his power of purchasing tea at 2s. a pound. . .

When at last the price has fallen to 2s. he buys seven pounds,

which are severally worth to him not less than 20, 14, 10, 6,

4, 3, and 2s. or 59s. in all. This sum measures their total

utility to him, and his consumer's surplus is (at least) the

excess of this sum over the 14s. he actually does pay for

them, i.e. 45s. This is the excess value of the satisfaction

he gets from buying the tea over that which he could have got

by spending the 14s. in extending a little his purchase of

other commodities, of which he had just not thought it worth

while to buy more at their current prices; and any further

purchases of which at those prices would not yield him any

consumer's surplus. In other words, he derives this 45s. worth

of surplus enjoyment from his conjuncture, from the adaptation

of the environment to his wants in the particular matter of

tea.

p. 132a

4. The substance of our argument would not be affected if we took

account of the fact that, the

more a person spends on anything the less power he retains

of purchasing more of it or of other things, and the greater

is the value of money to him (in the technical

language every fresh expenditure increases the marginal value

of money to him). But though its substance would not be

altered, its form would be made more intricate without any

corresponding gain; for there are very few practical problems,

in which the corrections to be made under this head would be

of any importance.

There are however some exceptions. For

instance, as Sir R. Giffen has pointed out, a rise in the

price of bread makes so large a drain on the resources of the

poorer labouring families and raises so much the marginal

utility of money to them, that they are forced to curtail

their consumption of meat and the more expensive farinaceous

foods: and, bread being still the cheapest food which they can

get and will take, they consume more, and not less of it. But

such cases are rare; when they are met with, each must be

treated on its own merits.

p. 136a

In every civilized country there have been

some followers of the Buddhist doctrine that a placid serenity

is the highest ideal of life; that it is the part of the wise

man to root out of his nature as many wants and desires as he

can; that real riches

consist not in the abundance of goods but in the paucity of

wants. At the other extreme are those who maintain

that the growth of new wants and desires is always beneficial

because it stimulates people to increased exertions. They seem

to have made the mistake, as Herbert Spencer says, of

supposing that life is for working, instead of working for

life.

The truth seems to be that as human nature

is constituted, man rapidly

degenerates unless he has some hard work to do, some

difficulties to overcome; and that some strenuous exertion is

necessary for physical and moral health. The fulness of life

lies in the development and activity of as many and as high

faculties as possible. . .

|