|

Jeremy Bentham

& John Stuart Mill

Jeremy Bentham Born in London 1748, he was a

child prodigy, the child of a prosperous attorney. He

began to study Latin at age three, and entered Queen's College

Oxford at age 12 to study law. Bentham is remembered as the father of Utilitarianism, promoting `the greatest happiness of the greatest number'. Based on this doctrine, he supported:

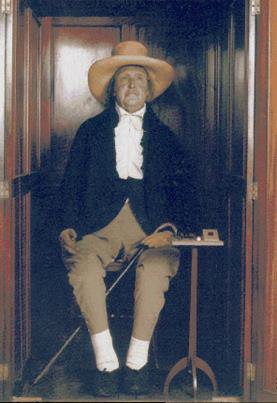

The Auto-Icon http://www.ucl.ac.uk/Bentham-Project/info/jb.htm Shortly before he died in

1832, Bentham requested in his will that his body be preserved

and displayed. The first two photos are in the original

cabinet, and the first includes the shrunken head. The new

clear cabinet was built in 2020. * * *

Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation By Jeremy Bentham Chapter I Of The Principle Of Utility http://www.la.utexas.edu/research/poltheory/bentham/ipml/ipml.c01.html#c01p01 Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do. On the one hand the standard of right and wrong, on the other the chain of causes and effects, are fastened to their throne. They govern us in all we do, in all we say, in all we think: every effort we can make to throw off our subjection, will serve but to demonstrate and confirm it. In words a man may pretend to abjure their empire: but in reality he will remain. subject to it all the while.

Chapter IV Value of a Lot of Pleasure or Pain, how to be Measured <http://www.la.utexas.edu/research/poltheory/bentham/ipml/ipml.c04.html#c04p05> I. Pleasures then, and the avoidance of pains, are the ends that the legislator has in view; it behoves him therefore to understand their value. Pleasures and pains are the instruments he has to work with: it behoves him therefore to understand their force, which is again, in other words, their value. II. To a person considered by himself, the value of a pleasure or pain considered by itself, will be greater or less, according to the four following circumstances:

III. These are the circumstances which are to be considered in estimating a pleasure or a pain considered each of them by itself. But when the value of any pleasure or pain is considered for the purpose of estimating the tendency of any act by which it is produced, there are two other circumstances to be taken into the account; these are, 5. Its fecundity, or the chance it has of being followed by sensations of the same kind: that is, pleasures, if it be a pleasure: pains, if it be a pain. 6. Its purity, or the chance it has of not being followed by sensations of the opposite kind: that is, pains, if it be a pleasure: pleasures, if it be a pain. These two last, however, are in strictness scarcely to be deemed properties of the pleasure or the pain itself; they are not, therefore, in strictness to be taken into the account of the value of that pleasure or that pain. They are in strictness to be deemed properties only of the act, or other event, by which such pleasure or pain has been produced; and accordingly are only to be taken into the account of the tendency of such act or such event. IV. To a number of persons, with reference to each of whom to the value of a pleasure or a pain is considered, it will be greater or less, according to seven circumstances: to wit, the six preceding ones; viz.

V. To take an exact account then of the general tendency of any act, by which the interests of a community are affected, proceed as follows. Begin with any one person of those whose interests seem most immediately to be affected by it: and take an account,

It is not to be expected that this process should be strictly pursued previously to every moral judgment, or to every legislative or judicial operation. It may, however, be always kept in view: and as near as the process actually pursued on these occasions approaches to it, so near will such process approach to the character of an exact one. * * *

Other utilitarian principles: In political terms, "greatest good for the greatest number" requires: o Universal suffrage o One person-one vote o Freedom of speech and press And, in later works of J.S. Mill o Public education

1806 - Born

in Pentonville (northern London). Intense early classical and

utilitarian education by his father, James Mill. Read Smith

and Ricardo as a teenager, and Ricardo was a family friend. 1820 - Spent

a year in France, exposed to a wide range of new ideas,

including those of democratic socialists, such as Henri

Saint-Simon and

Charles Fourier. Fourier (1772-1837) was one of the

first feminist writers (in fact, he is credited with coining

that term), calling for a full range of women's rights (and

also what we would now call LGBTQ+ rights), and proposed a

model of communitarian socialism organized around

self-sufficient "phalansteries."

At one time, there were hundreds of communities in the U.S.

based on this model, including Brook

Farm in Massachusetts (home of Nathaniel Hawthorne) and

La

Reunion in Dallas, Texas - the namesake of Reunion

Tower. 1823 - 1858 -

Served in administration for the British East India Company,

but never traveled to India. 1829 -

Suffered depression and considered suicide, but was comforted

by the poetry of Wadsworth,

and began a re-evaluation of utilitarianism. 1830 - Mill's

recovery was also encouraged by the beginning

of an intimate and intellectual friendshi 1843 – A System of Logic:

Formulated five principles of inductive reasoning – causal

inference - that are known as Mill's Methods. 1848 –

Principles of Political Economy: We'll look at that in

some detail 1851-1858 -

Married Harriet Taylor after the death of her husband, but she

died at age 51. 1859 – On

Liberty: “The only purpose for which power can be

rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community,

against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good,

either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant.” 1861 – Utilitarianism:

Updated Benthamism – pleasures differ not only in quantity,

but in quality. 1861 – Considerations

on Representative Government: Included support of

women’s suffrage. 1865-1868 -

Served as Rector of St Andrews School and also served as a

member of Parliament, calling for social reforms, including

legal rights for labour unions and farm cooperatives. 1869 – The

Subjection of Women: One of the first books by a man

calling for full equality of women in legal rights and

education and made early arguments against domestic violence.

Also called for abolition of slavery in the U.S. and

elsewhere. 1873 - Died and buried in Avignon, France,

beside his beloved Harriet.

The Principles of Political Economy by John Stuart Mill Book IIDISTRIBUTIONChapter IOf Propertyp. 5 1. The principles which have been set forth in the first part of this treatise, are, in certain respects, strongly distinguished from those on the consideration of which we are now about to enter. The laws and conditions of the Production of wealth partake of the character of physical truths. There is nothing optional or arbitrary in them. Whatever mankind produce, must be produced in the modes, and under the conditions, imposed by the constitution of external things, and by the inherent properties of their own bodily and mental structure. It is not so with the Distribution of wealth. That is a matter of human institution solely. The things once there, mankind, individually or collectively, can do with them as they like... The distribution of wealth, therefore, depends on the laws and customs of society. The rules by which it is determined, are what the opinions and feelings of the ruling portion of the community make them, and are very different in different ages and countries; and might be still more different, if mankind so chose. II.1.2 The opinions and feelings of mankind, doubtless, are not a matter of chance. They are consequences of the fundamental laws of human nature, combined with the existing state of knowledge and experience, and the existing condition of social institutions and intellectual and moral culture. 2. Private property, as an institution, did not owe its origin to any of those considerations of utility, which plead for the maintenance of it when established. Enough is known of rude ages, both from history and from analogous states of society in our own time, to show that tribunals (which always precede laws) were originally established, not to determine rights, but to repress violence and terminate quarrels. With this object chiefly in view, they naturally enough gave legal effect to first occupancy, by treating as the aggressor the person who first commenced violence, by turning, or attempting to turn, another out of possession. The preservation of the peace, which was the original object of civil government, was thus attained: while by confirming, to those who already possessed it, even what was not the fruit of personal exertion, a guarantee was incidentally given to them and others that they would be protected in what was so. II.1.5 The assailants of the principle of individual property may be divided into two classes: those whose scheme implies absolute equality in the distribution of the physical means of life and enjoyment, and those who admit inequality, but grounded on some principle, or supposed principle, of justice or general expediency, and not, like so many of the existing social inequalities, dependent on accident alone. At the head of the first class, as the earliest of those belonging to the present generation, must be placed Mr. Owen and his followers. M. Louis Blanc and M. Cabet have more recently become conspicuous as apostles of similar doctrines... The characteristic name for this economical system is Communism, a word of continental origin, only of late introduced into this country. The word Socialism, which originated among the English Communists, and was assumed by them as a name to designate their own doctrine, is now [1849], on the Continent, employed in a larger sense; not necessarily implying Communism, or the entire abolition of private property, but applied to any system which requires that the land and the instruments of production should be the property, not of individuals, but of communities or associations, or of the government. Among such systems, the two of highest intellectual pretension are those which, from the names of their real or reputed authors, have been called St. Simonism and Fourierism; the former defunct as a system, but which during the few years of its public promulgation, sowed the seeds of nearly all the Socialist tendencies which have since spread so widely in France: the second, still flourishing in the number, talent, and zeal of its adherents. II.1.9 3. Whatever may be the merits or defects of these various schemes, they cannot be truly said to be impracticable. No reasonable person can doubt that a village community, composed of a few thousand inhabitants cultivating in joint ownership the same extent of land which at present feeds that number of people, and producing by combined labour and the most improved processes the manufactured articles which they required, could raise an amount of productions sufficient to maintain them in comfort; and would find the means of obtaining, and if need be, exacting, the quantity of labour necessary for this purpose, from every member of the association who was capable of work. II.1.10 The objection ordinarily made to a system of community of property and equal distribution of the produce, that each person would be incessantly occupied in evading his fair share of the work, points, undoubtedly, to a real difficulty. But those who urge this objection, forget to how great an extent the same difficulty exists under the system on which nine-tenths of the business of society is now conducted… If Communistic labour might be less vigorous than that of a peasant proprietor, or a workman labouring on his own account, it would probably be more energetic than that of a labourer for hire, who has no personal interest in the matter at all… II.1.11 A contest, who can do most for the common good, is not the kind of competition which Socialists repudiate. To what extent, therefore, the energy of labour would be diminished by Communism, or whether in the long run it would be diminished at all, must be considered for the present an undecided question. II.1.12 Another of the objections to Communism is similar to that so often urged against poor laws: that if every member of the community were assured of subsistence for himself and any number of children, on the sole condition of willingness to work, prudential restraint on the multiplication of mankind would be at an end, and population would start forward at a rate which would reduce the community, through successive stages of increasing discomfort, to actual starvation… But Communism is precisely the state of things in which opinion might be expected to declare itself with greatest intensity against this kind of selfish intemperance… II.1.13 A more real difficulty is that of fairly apportioning the labour of the community among its members. There are many kinds of work, and by what standard are they to be measured one against another? Who is to judge how much cotton spinning, or distributing goods from the stores, or bricklaying, or chimney sweeping, is equivalent to so much ploughing? The difficulty of making the adjustment between different qualities of labour is so strongly felt by Communist writers, that they have usually thought it necessary to provide that all should work by turns at every description of useful labour: an arrangement which, by putting an end to the division of employments, would sacrifice so much of the advantage of co-operative production as greatly to diminish the productiveness of labour… II.1.14 If, therefore, the choice were to be made between Communism with all its chances, and the present [1852] state of society with all its sufferings and injustices; if the institution of private property necessarily carried with it as a consequence, that the produce of labour should be apportioned as we now see it, almost in an inverse ratio to the labour—the largest portions to those who have never worked at all, the next largest to those whose work is almost nominal, and so in a descending scale, the remuneration dwindling as the work grows harder and more disagreeable, until the most fatiguing and exhausting bodily labour cannot count with certainty on being able to earn even the necessaries of life; if this or Communism were the alternative, all the difficulties, great or small, of Communism would be but as dust in the balance. But to make the comparison applicable, we must compare Communism at its best, with the régime of individual property, not as it is, but as it might be made… That all should indeed start on perfectly equal terms, is inconsistent with any law of private property: but if as much pains as has been taken to aggravate the inequality of chances arising from the natural working of the principle, had been taken to temper that inequality by every means not subversive of the principle itself; if the tendency of legislation had been to favour the diffusion, instead of the concentration of wealth—to encourage the subdivision of the large masses, instead of striving to keep them together; the principle of individual property would have been found to have no necessary connexion with the physical and social evils which almost all Socialist writers assume to be inseparable from it… II.1.16 To judge of the final destination of the institution of property, we must suppose everything rectified, which causes the institution to work in a manner opposed to that equitable principle, of proportion between remuneration and exertion, on which in every vindication of it that will bear the light, it is assumed to be grounded. We must also suppose two conditions realized, without which neither Communism nor any other laws or institutions could make the condition of the mass of mankind other than degraded and miserable. One of these conditions is universal education; the other, a due limitation of the numbers of the community. With these there could be no poverty, even under the present social institutions: and these being supposed, the question of Socialism is not, as generally stated by Socialists, a question of flying to the sole refuge against the evils which now bear down humanity; but a mere question of comparative advantages, which futurity must determine. We are too ignorant either of what individual agency in its best form, or Socialism in its best form, can accomplish, to be qualified to decide which of the two will be the ultimate form of human society. II.1.17 If a conjecture may be hazarded, the decision will probably depend mainly on one consideration, viz. which of the two systems is consistent with the greatest amount of human liberty and spontaneity. After the means of subsistence are assured, the next in strength of the personal wants of human beings is liberty; and (unlike the physical wants, which as civilization advances become more moderate and more amenable to control) it increases instead of diminishing in intensity, as the intelligence and the moral faculties are more developed… It remains to be discovered how far the preservation of this characteristic would be found compatible with the Communistic organization of society. No doubt, this, like all the other objections to the Socialist schemes, is vastly exaggerated… The question is, whether there would be any asylum left for individuality of character; whether public opinion would not be a tyrannical yoke; whether the absolute dependence of each on all, and surveillance of each by all, would not grind all down into a tame uniformity of thoughts, feelings, and actions.

|

John

Stuart Mill

John

Stuart Mill