|

An Inquiry into the

Nature and Causes by

Adam Smith 1776 Book

1, Chapter 6 OF

THE COMPONENT PARTS OF THE PRICE

OF COMMODITIES

In that early and rude state of

society which precedes both the accumulation of stock and

the appropriation of land, the proportion between the

quantities of labour necessary for acquiring different

objects seems to be the only circumstance which can afford

any rule for exchanging them for one another. If among a

nation of hunters, for example, it usually costs twice the

labour to kill a beaver which it does to kill a deer, one

beaver should naturally exchange for or be worth two deer. [I, vi, 4, p. 65] In this state of things, the

whole produce of labour belongs to the labourer; and the

quantity of labour commonly employed in acquiring or

producing any commodity is the only circumstance which can

regulate the quantity exchange for which it ought commonly

to purchase, command, or exchange for. As soon as stock has accumulated

in the hands of particular persons, some of them will

naturally employ it in setting to work industrious people,

whom they will supply with materials and subsistence, in

order to make a profit... In exchanging the complete

manufacture either for money, for labour, or for other

goods, over and above what may be sufficient to pay the

price of the materials, and the wages of the workmen,

something must be given for the profits of the undertaker of

the work who hazards his stock in this adventure... He could

have no interest to employ them, unless he expected from the

sale of their work something more than what was sufficient

to replace his stock to him; and he could have no interest

to employ a great stock rather than a small one, unless his

profits were to bear some proportion to the extent of his

stock. [I, vi, 8, p. 67] As soon as the land of any

country has all become private property, the landlords, like

all other men, love to reap where they never sowed, and

demand a rent even for its natural produce... This portion,

or, what comes to the same thing, the price of this portion,

constitutes the rent of land, and in the price of the

greater part of commodities makes a third component part. The real value of all the

different component parts of price, it must be observed, is

measured by the

quantity of labour which they can, each of them, purchase or

command. Labour measures the value not only of that part of

price which resolves itself into labour, but of that which

resolves itself into rent, and of that which resolves itself

into profit. Book

1, Chapter 7 OF

THE NATURAL AND MARKET PRICE

OF COMMODITIES

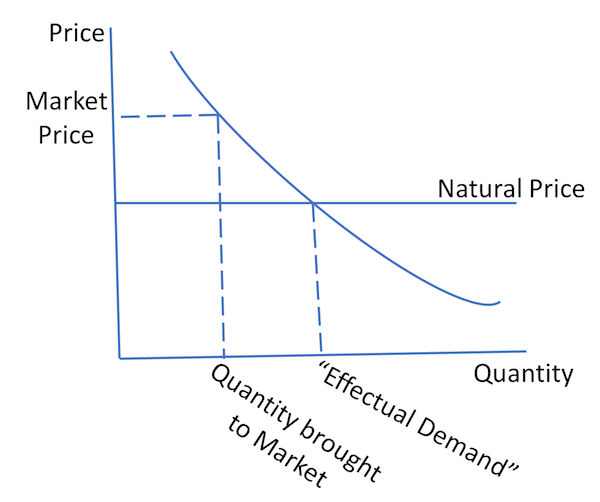

There is likewise in every

society or neighbourhood an ordinary or average rate of

rent, which is regulated too, as I shall show hereafter,

partly by the general circumstances of the society or

neighbourhood in which the land is situated, and partly by

the natural or improved fertility of the land. These ordinary or average rates

may be called the natural rates of wages, profit, and rent,

at the time and place in which they commonly prevail. When the price of any commodity

is neither more nor less than what is sufficient to pay the

rent of the land, the wages of the labour, and the profits

of the stock employed in raising, preparing, and bringing it

to market, according to their natural rates, the commodity

is then sold for what may be called its natural price. [I, vii, 7, p. 73] The market price of every

particular commodity is regulated by the proportion between

the quantity which is actually brought to market, and the

demand of those who are willing to pay the natural price of

the commodity, or the whole value of the rent, labour, and

profit, which must be paid in order to bring it thither.

Such people may be called the effectual demanders, and their

demand the effectual demand; since it may be sufficient to

effectuate the bringing of the commodity to market. It is

different from the absolute demand... When the quantity of any commodity which is brought to market falls short of the effectual demand, all those who are willing to pay the whole value of the rent, wages, and profit, which must be paid in order to bring it thither, cannot be supplied with the quantity which they want. Rather than want it altogether, some of them will be willing to give more. A competition will immediately begin among them, and the market price will rise more or less above the natural price, according as either the greatness of the deficiency, or the wealth and wanton luxury of the competitors, happen to animate more or less the eagerness of the competition. . .  [I, vii, 12, p. 74] If at any time it exceeds the

effectual demand, some of the component parts of its price

must be paid below their natural rate. If it is rent, the

interest of the landlords will immediately prompt them to

withdraw a part of their land; and if it is wages or profit,

the interest of the labourers in the one case, and of their

employers in the other, will prompt them to withdraw a part

of their labour or stock from this employment. The quantity

brought to market will soon be no more than sufficient to

supply the effectual demand. All the different parts of its

price will rise to their natural rate, and the whole price

to its natural price. . . [I, vii, 15, p. 75] [I, vii, 33, p. 80] Book

1, Chapter 8 OF

THE WAGES OF LABOUR

In that original state of

things, which precedes both the appropriation of land and

the accumulation of stock, the whole produce of labour

belongs to the labourer. He has neither landlord nor master

to share with him. [I, viii, 6, p. 83] It seldom happens that the

person who tills the ground has wherewithal to maintain

himself till he reaps the harvest. His maintenance is

generally advanced to him from the stock of a master, the

farmer who employs him, and who would have no interest to

employ him, unless he was to share in the produce of his

labour, or unless his stock was to be replaced to him with a

profit. This profit, makes a second deduction from the

produce of the labour which is employed upon land. [I, viii, 11, p. 83] It is not, however, difficult to foresee which of the two parties must, upon all ordinary occasions, have the advantage in the dispute, and force the other into a compliance with their terms. The masters, being fewer in number, can combine much more easily; and the law, besides, authorizes, or at least does not prohibit their combinations, while it prohibits those of the workmen. We have no acts of parliament against combining to lower the price of work; but many against combining to raise it. In all such disputes the masters can hold out much longer... We rarely hear, it has been said, of the combinations of masters, though frequently of those of workmen. But whoever imagines, upon this account, that masters rarely combine, is as ignorant of the world as of the subject. Masters are always and everywhere in a sort of tacit, but constant and uniform combination, not to raise the wages of labour above their actual rate. To violate this combination is everywhere a most unpopular action, and a sort of reproach to a master among his neighbours and equals... But though in disputes with

their workmen, masters must generally have the advantage,

there is, however, a certain rate below which it seems

impossible to reduce, for any considerable time, the

ordinary wages even of the lowest species of labour. A man must always live by his

work, and his wages must at least be sufficient to maintain

him. They must even upon most occasions be somewhat more;

otherwise it would be impossible for him to bring up a

family, and the race of such workmen could not last beyond

the first generation. . . There are certain circumstances,

however, which sometimes give the labourers an advantage,

and enable them to raise their wages considerably above this

rate; evidently the lowest which is consistent with common

humanity. When in any country the demand

for those who live by wages, labourers, journeymen, servants

of every kind, is continually increasing; when every year

furnishes employment for a greater number than had been

employed the year before, the workmen have no occasion to

combine in order to raise their wages. The scarcity of hands

occasions a competition among masters, who bid against one

another, in order to get workmen, and thus voluntarily break

through the natural combination of masters not to raise

wages. The demand for those who live by

wages, it is evident, cannot increase but in proportion to

the increase of the funds which are destined for the payment

of wages. These funds are of two kinds; first, revenue which

is over and above what is necessary for the maintenance;

and, secondly, the stock which is over and above what is

necessary for the employment of their masters. [I, viii, 22, p. 87] [I, viii, 24, p. 89] [I, viii, 38, p. 97]

Book 1, Chapter 9 [I, ix, 1, p. 105]

By the 37th of Henry VIII

all interest above ten per cent was declared unlawful. More,

it seems, had sometimes been taken before that. In the reign

of Edward VI religious zeal prohibited all interest. This

prohibition, however, like all others of the same kind, is

said to have produced no effect, and probably rather increased

than diminished the evil of usury. The statute of Henry VIII

was revived by the 13th of Elizabeth, c. 8, and ten per cent

continued to be the legal rate of interest till the 21st of

James I, when it was restricted to eight per cent. It was

reduced to six per cent soon after the Restoration, and by the

12th of Queen Anne to five per cent. All these different

statutory regulations seem to have been made with great

propriety. They seem to have followed and not to have gone

before the market rate of interest, or the rate at which

people of good credit usually borrowed. Since the time of

Queen Anne, five per cent seems to have been rather above than

below the market rate. Before the late war, the government

borrowed at three per cent; and people of good credit in the

capital, and in many other parts of the kingdom, at three and

a half, four, and four and a half per cent.

Book 1, Chapter 10 OF WAGES AND PROFIT IN THE DIFFERENT EMPLOYMENTS OF LABOUR AND STOCK

[I, x, Part 3, 22, p. 142] The inhabitants of a town, being collected into one place, can easily combine together... [I, x, Part 3, 23, p. 143] [I, x, Part 3, 27, p. 145]

Book 1, Chapter 11 OF THE RENT OF LAND [I, xi, 1, p. 160]

NOTE: Smith's theory of rent is,

perhaps, the biggest flaw in his overall theory of value.

Earlier, he promised to explain "natural price" by giving us

self-standing theories of wages, profits, and rents, and

then adding them together: Natural Price = Natural Wages

+ Natural Profits + Natural Rents But now, he has broken the promise, and says his theory of rent is: Rent = Price - Wages - Profits If he doesn't give us a

self-standing theory of Rent, then he hasn't given us a full

theory of Prices. So we will see that David Ricardo will

attempt to solve that problem. Book 2, Chapter 3 [II, iii, 16, p. 337] What is

annually saved is as regularly consumed as what is annually

spent, and nearly in the same time too; but it is consumed by

a different set of people. That portion of his revenue which a

rich man annually spends is in most cases consumed by idle

guests and menial servants, who leave nothing behind them in

return for their consumption. That portion which he annually

saves, as for the sake of the profit it is immediately

employed as a capital, is consumed in the same manner, and

nearly in the same time too, but by a different set of people,

by labourers, manufacturers, and artificers, who reproduce

with a profit the value of their annual consumption. His

revenue, we shall suppose, is paid him in money. Had he spent

the whole, the food, clothing, and lodging, which the whole

could have purchased, would have been distributed among the

former set of people. By saving a part of it, as that part is

for the sake of the profit immediately employed as a capital

either by himself or by some other person, the food, clothing,

and lodging, which may be purchased with it, are necessarily

reserved for the latter. The consumption is the same, but the

consumers are different. [II, iii, 27, p. 341] [II, iii, 28, p. 342] [II, iii, 30, p. 342] [II, iii, 31, p. 342] |