|

The Principles of Political

Economy Book 3 Of Demand and Supply in Their Relation to Value

The supply of a commodity is an intelligible expression: it means the quantity offered for sale; the quantity that is to be had, at a given time and place, by those who wish to purchase it. But what is meant by the demand? Not the mere desire for the commodity. A beggar may desire a diamond; but his desire, however great, will have no influence on the price. Writers have therefore given a more limited sense to demand, and have defined it, the wish to possess, combined with the power of purchasing. To distinguish demand in this technical sense, from the demand which is synonymous with desire, they call the former effectual demand. After this explanation, it is usually supposed that there remains no further difficulty, and that the value depends upon the ratio between the effectual demand, as thus defined, and the supply. These phrases, however, fail to satisfy any one who requires clear ideas, and a perfectly precise expression of them. Some confusion must always attach to a phrase so inappropriate as that of a ratio between two things not of the same denomination. What ratio can there be between a quantity and a desire, or even a desire combined with a power? A ratio between demand and supply is only intelligible if by demand we mean the quantity demanded, and if the ratio intended is that between the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied. But again, the quantity demanded is not a fixed quantity, even at the same time and place; it varies according to the value; if the thing is cheap, there is usually a demand for more of it than when it is dear. The demand, therefore, partly depends on the value. But it was before laid down that the value depends on the demand. From this contradiction how shall we extricate ourselves? How solve the paradox, of two things, each depending upon the other? . . .

Book 3: Distribution Of Some Peculiar Cases of Value

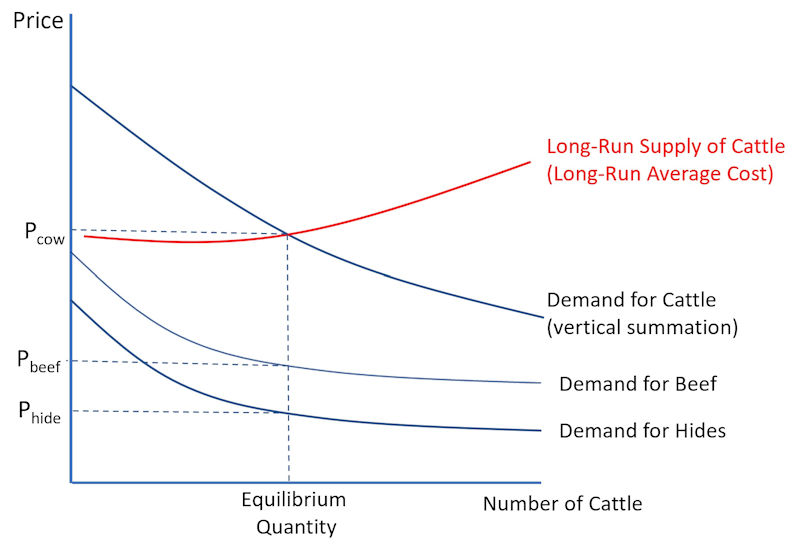

It sometimes

happens that two different commodities have what may be termed

a joint cost of production. They are both products of the same

operation, or set of operations, and the outlay is incurred

for the sake of both together, not part for one and part for

the other. The same outlay would have to be incurred for

either of the two, if the other were not wanted or used at

all. There are not a few instances of commodities thus

associated in their production. For example, coke and coal-gas

are both produced from the same material, and by the same

operation. In a more partial sense, mutton and wool are an

example: beef, hides, and tallow: calves and dairy produce:

chickens and eggs. Cost of production can have nothing to do

with deciding the value of the associated commodities

relatively to each other. It only decides their joint value.

The gas and the coke together have to repay the expenses of

their production, with the ordinary profit. . . . Cost of

production does not determine their prices, but the sum of

their prices. A principle is wanting to apportion the expenses

of production between the two.

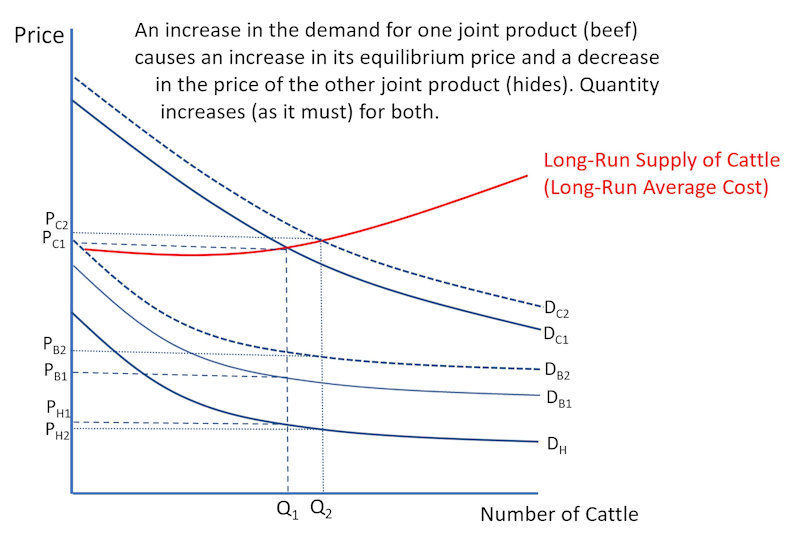

. . . Suppose ... that more coke is wanted at the present prices, than can be supplied by the operations required by the existing demand for gas. Coke, being now in deficiency, will rise in price. The whole operation will yield more than the usual rate of profit, and additional capital will be attracted to the manufacture. The unsatisfied demand for coke will be supplied; but this cannot be done without increasing the supply of gas too; and as the existing demand was fully supplied already, an increased quantity can only find a market by lowering the price. The result will be that the two together will yield the return required by their joint cost of production, but that more of this return than before will be furnished by the coke, and less by the gas. Equilibrium will be attained when the demand for each article fits so well with the demand for the other, that the quantity required of each is exactly as much as is generated in producing the quantity required of the other. If there is any surplus or deficiency on either side; if there is a demand for coke, and not a demand for all the gas produced along with it, or vice versa; the values and prices of the two things will so readjust themselves that both shall find a market. . .

Essays

on Some Unsettled

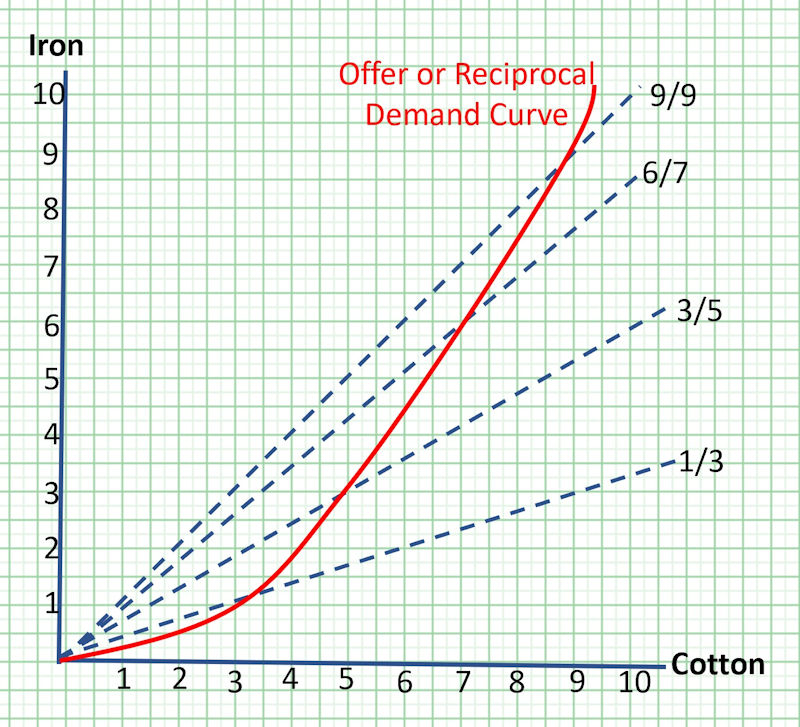

It is established, that the

advantage which two countries derive from trading with each

other, results from the more advantageous employment which

thence arises, of the labour and capital—for shortness let us

say the labour—of both jointly. The circumstances are such,

that if each country confines itself to the production of one

commodity, there is a greater total return to the labour of

both together; and this increase of produce forms the whole of

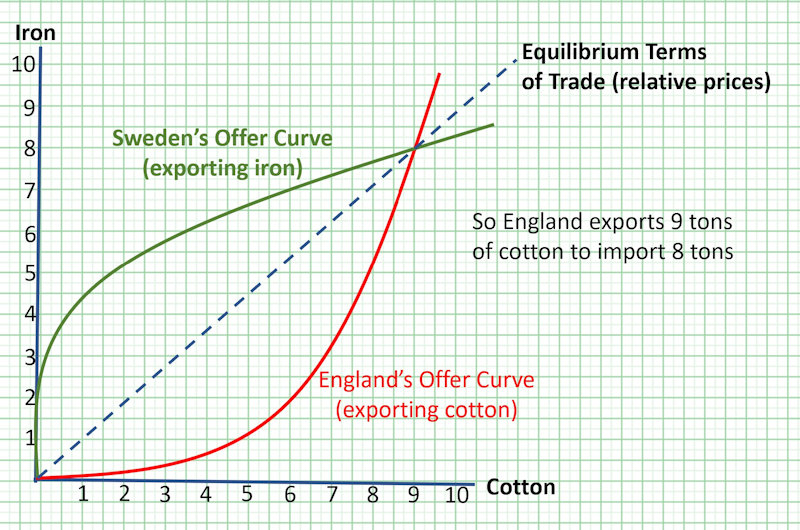

what the two countries taken together gain by the trade. Gardner: Mill's theory of "reciprocal demand" was later formalized into graphs by Frances Edgeworth and Alfred Marshall in "offer curves" or "reciprocal demand curves" that are explained more fully in international economics courses:

|