|

Sweden: Whither the Welfare State?

I.

The Environment

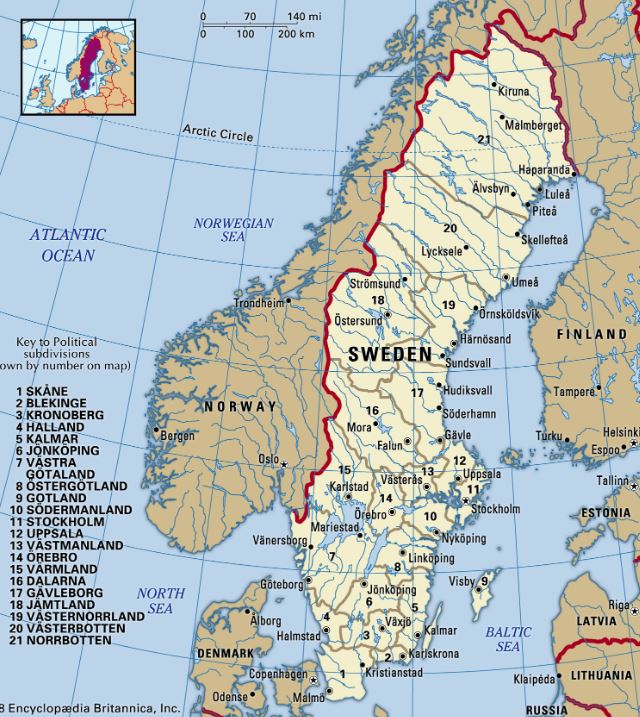

A. Geography

- Relatively isolated; allowed Swedes to avoid major war since

1813. Rich endowment of timber, and iron ore and other

natural resources.

B. Sociological

- Small population - 10.5 million, much smaller than Texas

(30m), but larger than Denmark (5.9m), Norway (5.5m), or

Finland (5.5m). Historically, geographic isolation contributed

to cultural homogeneity - in 1900 only 1% of the population

was foreign born. Welfare programs did not seem to distribute

income from one group to another, supporting the growth of the

welfare state. The foreign-born share grew to 14% in 2010 and

20% today, sparking a populist backlash.

C.  Political

- Dominant since 1932, the Social Democratic Party lost

control during 1936, 1976-1982, 1991-1995, 2006-2014, and

currently since October 2022 when Ulf Kristersson from the

Moderate party formed a coalition of right-leaning parties

with the Sweden Democrats, Christian Democrats, and Liberals

that gained power after a general election. The Sweden

Democrats, now the largest of the coalition parties in the

Riksdag parliament (although the Social Democrats are still

the largest single party overall) is an anti-immigrant ("Keep

Sweden Swedish") right-wing populist party, and the policies

of the current government largely reflect its values. Political

- Dominant since 1932, the Social Democratic Party lost

control during 1936, 1976-1982, 1991-1995, 2006-2014, and

currently since October 2022 when Ulf Kristersson from the

Moderate party formed a coalition of right-leaning parties

with the Sweden Democrats, Christian Democrats, and Liberals

that gained power after a general election. The Sweden

Democrats, now the largest of the coalition parties in the

Riksdag parliament (although the Social Democrats are still

the largest single party overall) is an anti-immigrant ("Keep

Sweden Swedish") right-wing populist party, and the policies

of the current government largely reflect its values.

II.

Industrial Organization

A. Nationalization

- SDP philosophy did not call for the nationalization of

industry. Some were nationalized to prevent them from

facing bankruptcy, but some of those have been returned to

private hands.

B. Monopolies

and Industrial Concentration - Small domestic market

contributes to high industrial concentration ratios.

Dominance of small number of large multinational

companies. Still, a high level of foreign competition

and extensive system of consumer cooperatives.

III. The Labor Market and Labor Relations

A. Collective

Bargaining -

1.

Basic Agreement - Swedish Confederation of Trade Unions

(LO) formed in 1898, and Swedish Employers Association (SAF)

formed in 1902. In 1938, employers and labor accepted

the Basic Agreement of Saltsjobaden, under which management

recognized the labor unions and established general rules

about layoffs and dismissals. Both sides agreed to hold

direct negotiations before resorting to strikes or lockouts.

2.

Centralized bargaining - Developed after World War

II. Employers wanted more orderly bargaining.

Unions wanted wage solidarity (largest wage increases

to the lowest-paid workers). Wage negotiations take

place at the national level and result in a binding

framework. Local negotiations are held between

employers' groups and union affiliates.

3.

Evaluation - 1945-1970, central bargaining worked

well. In 1970 departures from the central agreement

became common and inflation rose above the average of other

industrial countries. Disagreements over wage solidarity

have weakened the system, leading to independent action by

machine workers (who had been sacrificing larger pay raises),

and centralized bargaining was replaced by standard

industry-level bargaining in 1983..

B. Active

Labor Market Policy - Includes programs to increase the

demand for labor, training programs to tailor labor supply to

new job openings, and to match supply and demand through job

information and placement services. National and 24

regional Labor Market Boards. Unemployment benefits are

less generous in Sweden than OECD average.

In 2017, as % of GDP, expenditures on active programs

were 0.1% in the U.S., 0.52% as an OECD average, 0.65% in

Germany, 0.87% in France, 1.25% in Sweden, and 1.96% in

Denmark. On the other hand, expenditures on passive programs

(unemployment compensation) were 0.14% of GDP in the U.S.,

0.53% in Sweden, and 0.68% as an OECD average. (Source: OECD

Employment Outlook 2020).

C. Codetermination

and Employee Ownership - Workers participate in

management through works councils and representation on boards

of directors.

IV.

The Governmental Sector

A. Fiscal

and Monetary Policy - Even before the Depression,

policies designed to reduce unemployment were proposed in

Sweden.

1.

Investment reserve funds - allowed the government to

control rough one eighth of private investment by awarding tax

credits to companies that save during boom periods and invest

during downturns. According to Taylor, successfully

stabilized investment. Abolished in 1991.

2.

Monetary policy - the Riksbank once exercised direct

control over bank lending. In recent years, focus on inflation

reduction.

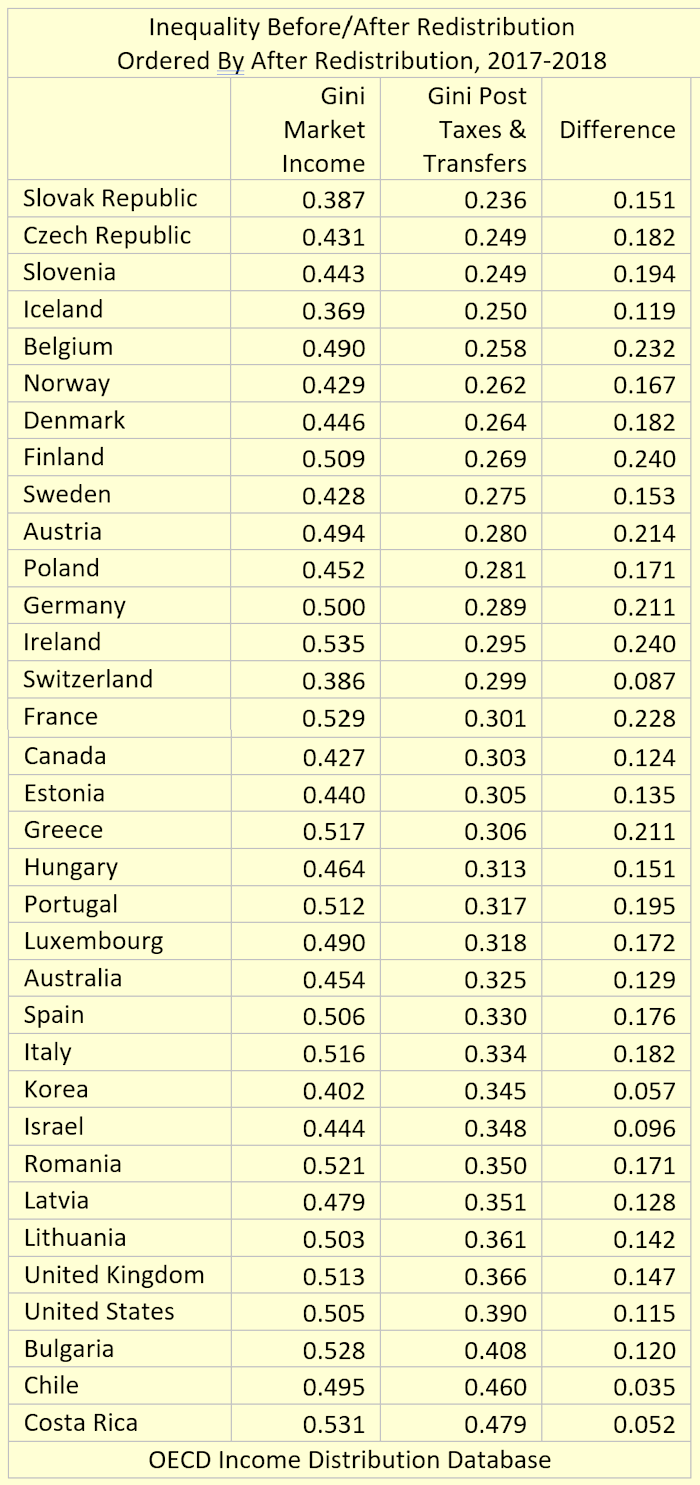

B. Social

Welfare and Income Redistribution - Although it no

longer has the highest level of spending in the world, Sweden

has an extensive welfare state that includes (excerpted

from here):

§ Family Care: Day-care and preschool

programs are almost free, with fees based on family income: If

parents are unemployed, child care is totally free. Swedish

pregnant women get free and subsidized prenatal care and

parents get 480 days of paid leave when a child is born or

adopted, which they can share (240 days each). (Sweden was the

first country to offer fathers paid parental leave, in 1974.)

Parents get about 80 percent of their salaries when they stay

home with a sick child (up to age 12). They can take this

temporary leave up to 120 days a year.

§ Education: Kindergarten through high

school is free, as are school lunches. Undergraduate

college/university tuition is also free. If students need

money for books, food, and housing, they get nearly

no-interest loans. Swedish undergraduates aged 16–20 also get

$136 monthly stipends during the school year. If their

families are low-income, they may get more.

On the efficiency side, Sweden has an extensive school-choice

system.

§ Medical Care: Medical and hospital care

are basically free until age 20. After then, doctor visits

cost Swedes $10 to $32, or up to $38 for specialists. After

people meet a $119 annual deductible, all care is free.

Moreover, medicine is free after a $239 yearly deductible.

Drugs are the same price at all pharmacies, so people needn’t

shop around for the best price.

§ Unemployment Benefits: Provided from the

government and from union insurance plans. The plans provide

80 percent of Swedes’ wages/salaries for the first 200 days

they’re out of work and 70 percent for the next 100.

§ Pensions: Pensions are covered by the

government or union/employer plans. If Swedes have low-paying

jobs (under $40,000 a year), the government and employers pay

into the plans, but the employees don’t contribute. If they

have middle- and higher-income jobs, they must contribute,

along with their employers.

§ Transportation Perks: Government subsidies

vary. For example, people pushing baby strollers or carriages

in some cities (such as Stockholm) ride for free on the buses.

In others (such as Gothenburg), retired Swedes pay nothing,

except during rush hours.

§ Housing Subsidies: Local governments

subsidize low-income and elderly Swedes’ rental housing and

also help them find it. The amount is based on their income

and the local cost of living. In large cities like Stockholm,

affordable housing is hard to find—whether to buy or rent (for

which the wait is long). Thus Swedes now live farther outside

the central cities and tend to buy their houses/apartments.

§ Wages: Sweden doesn’t have a minimum wage.

Instead, strong unions and employers negotiate wages/salaries.

This is particularly important for low-income workers: A

cashier at a Swedish McDonald’s was already earning $15 an

hour a few years ago.

§ Taxes: Swedes pay income tax to both

national and local governments. In fact, in 2017 Sweden had

the highest top marginal tax rate among OECD countries,

followed by Denmark, Japan, Greece, France, and Canada. In all

these countries, the top rate is over 50 percent. While some

Swedes grumble about their taxes, a 2017 OECD public opinion

poll (based on Gallup/World Bank data) found that 50 percent

trusted their government, while the figure was only 30 percent

for Americans.

Critics maintain that the high tax rates have damaged

incentives. The average Swedish work week is one of the

shortest in the world. High taxes have driven a

significant part of income and production underground in the

form of do-it-yourself home improvements and barter

activities.

Henrik Jacobsen Kleven addresses the question, "How

Can Scandinavians Tax So Much?" and finds (1) that tax

compliance rates are high in those countries, partly because

of 3rd-party reporting; (2) low levels of legal tax avoidance

due to a broad tax base that offers limited scope for reducing

tax liability through deductions and income shifting; and (3)

a fiscal system that spends relatively large amounts on

means-tested transfer programs that could reduce work

incentives, but also spends relatively large amounts on the

public provision and subsidization of goods that are

complementary to working, including child care, elderly care,

and transportation. "Such policies represent subsidies to the

costs of market work, which encourage labor supply and make

taxes less distortionary."

C. Covid-19

Response - Aside from closing its external

borders, Sweden was slow to take action against Covid-19. It's

the only country in Europe that never had a serious lockdown,

and relatively few people ever wore masks. The chief

epidemiologist was hoping to reach herd immunity quickly

without too many deaths, but the King declared it a failure.

Sweden has had fewer excess deaths than many other European

countries, but higher death rates than its neighbors.

|